|

FEATURE |

Flight of Legal Eagles

This article is a synopsis of an MBA study conducted last year by Samuel Ang. He completed an MBA (Distinction) with Imperial College in 2005, and is currently an MPA student at Harvard. He thanks the Law Society of Singapore for the assistance and support provided to this study. For further information on the article or the study, please write to [email protected].

Legal Profession in Crisis

Source: The Law Society of Singapore

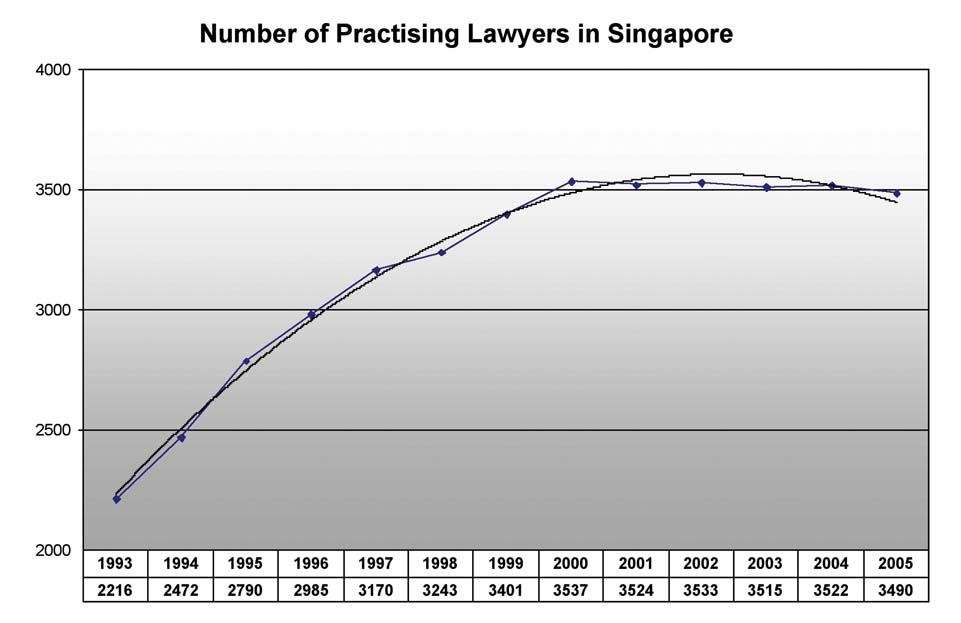

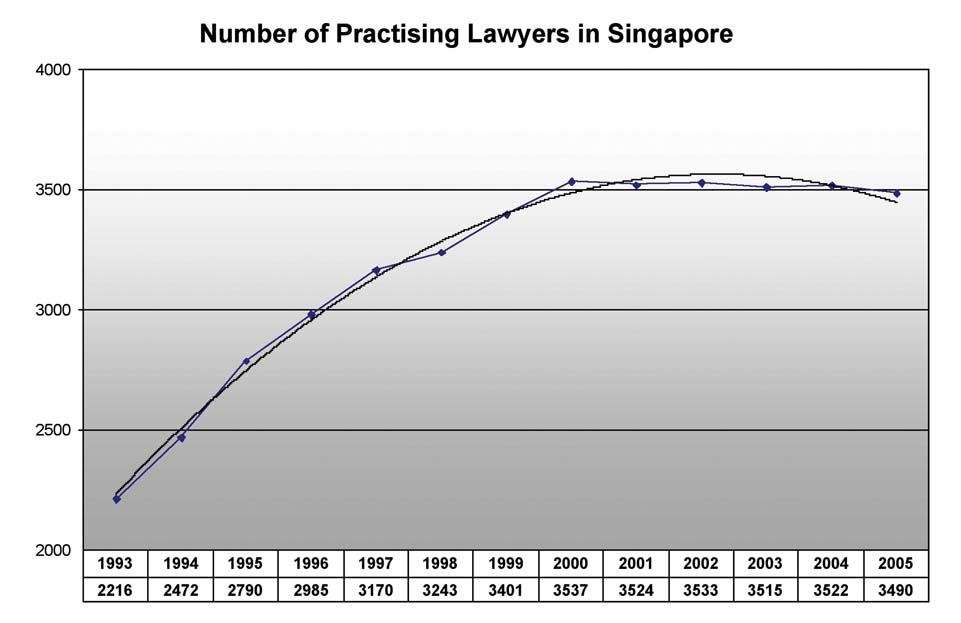

Singapore is facing a crisis in the increasing flight of lawyers from its legal profession. The number of practising lawyers rose steadily over the 1990s until 2001 when the Singapore Bar saw its first decline. In 2001, nearly 10 per cent (335 of over 3000 lawyers) of the Singapore Bar left practice. This brought about an unprecedented decrease in the Singapore legal profession. The subsequent five years have seen a trend in the growing number of lawyers that leave practice and a shrinking legal profession.

Attrition of young lawyers in Singapore

The Law Society of Singapore and the Ministry of Law have conducted surveys to find out why increasing numbers of lawyers leave practice. In the surveys, many ex-lawyers cited ‘stress due to pace of work, heavy workload and long working hours’ as reasons for leaving practice. Other factors include ‘lack of social life’ and ‘difficulty in balancing work and family life’. Notably, legal associates with under seven years’ experience comprise the majority of lawyers leaving the legal profession.

S

| Significant challenges faced in

practice by ex-lawyers |

|

Stress due to pace of work/workload 71 per cent Difficult client expectations/demands 55 per cent Insufficient/declining income 29 per cent Doubts about future of law practice 29 per cent Boredom, insufficient challenge 23 per cent Growing complexity in legal practice 23 per cent

Difficulty in dealing with changes in law and

practice 13 per cent Source: Survey by the Law Society of Singapore on Lawyers Leaving Practice2001 |

ignificant challenges faced in practice by ex-lawyers

| Reasons for ceasing practice by

young lawyers |

|

Heavy workload and long working hours 60 per cent Remuneration did not commensurate with workload 58 per cent To pursue other interests, aspirations or career 49 per cent Stress in dealing with clients 39 per cent Pace of litigation 35 per cent

Source: Ministry of Law Census of the Legal Industry and Profession 2001 |

Reasons for ceasing practice by young lawyers

The situation in other countries

Other legal jurisdictions face similar problems of attrition, long hours and stress. In the United Kingdom, a Law Society survey found that one in three London assistant solicitors intend to leave the law due to the long hours, unacceptable levels of stress and unrealistic billing targets. Likewise in the United States, 40 per cent of the estimated one million lawyers wished to do something else. The Boston Bar Association found an astonishingly high turnover rate among young associates. Of 154 law firms involving 10,000 associates surveyed, 10 per cent left within one year, 43 per cent left within three years, 67 per cent left within five years, and 75 per cent left within seven years. In Australia, 40 per cent of law graduates left the profession within five years of being admitted to practice due to excessively long hours, stress arising from too much work, lack of recognition and appreciation, and not enough time for family or social life.

Long Work Hours and Job Stress

Why long work hours?

The long work hours of the legal profession arises from the global intensification of workload impacting professional practice and the culture of presenteeism.

Intensifying workload and demands of professional practice

The internet age has seen three major global trends of access overload, information overload and work overload. Global intensification of workload directly impacts the legal industry, with law firms having to respond at similar pace, intensity and exacting demand levels to meet corporate business needs. The new globalised business environment brings to the legal industry a faster pace and heavier workload with correspondingly longer hours. Not only has workload intensified in the corporate world, the push for immediacy has invaded the profession. With electronic communications, every task now carries an immediacy that ratchets up the pressure on lawyers. Faxes and e-mails pressure lawyers to turn around documents within hours and days, unlike letters and documents sent via ‘snail mail’ of the past. Clients today expect lawyers to perform at electronic speed.

Technology has not only increased the pace of business, but further exacerbated the stress with unpredictable and on-call hours. This stress impacts especially younger lawyers and associates, vis-à-vis senior partners who have greater control over their workload and time. It is not only long hours per se, but the lack of control over the workload that junior lawyers find most stressful.

Culture of presenteeism

Another factor contributing to long hours in the legal profession is the culture of presenteeism, which may arise explicitly or implicitly in the law firm. The presenteeism culture traces to both extrinsic and intrinsic factors. Extrinsic factors such as billable hour requirements pressure lawyers to take on additional files or to do more work on existing files. Intrinsic peer competitiveness and ambition manifest with legal associates competing to outdo each other to demonstrate ‘visible commitment’ and thereby superior performance towards career advancement. Such attitudes could be attributable to law firms’ culture of success that tend to equate working long hours with ‘worth’, ‘commitment’ and ‘merit’. Even where law firms purposefully define merit by the quality of legal skills, responsiveness to client demands, commitment to the firm, and teamwork – these are all components of merit correlated with long hours and tend to be measured as such. For the problem of attrition and long hours, there is a need to address the extrinsic and intrinsic factors that contribute to this culture of presenteeism that may unjustifiably exacerbate long hours in the profession.

Why job stress and dissatisfaction?

Lawyers face many stressors at work. These include stress from:

1 Clients.

2 Courts.

3 Nature of practice.

4 Adversarial legal system.

Stress from difficult client demands and heightened pace of litigation need little exposition.

Job stress in legal practice also arises from work that is either too difficult, too much or too routine. This manifests in frustration from ‘qualitative overload’ arising from increasing complexity in legal practice, boredom from ‘qualitative underload’ in doing repetitive routine work, as well as burning out from ‘quantitative overload’ of excessive workloads.

Another reason for stress is that the legal profession could be an environment at odds with the individual lawyer’s personality. An adversarial legal system requires litigators to fight for their clients, which fosters anxiety and distrust of people. In this win-lose environment, some lawyers adopt a ‘Rambo litigator’ syndrome of hostility, manipulation, suspicion and cynicism. Lawyers uncomfortable with the demands of the adversarial legal system suffer cognitive dissonance between their internal values and the external environment, resulting in unhappiness and ultimately, withdrawal.

Beyond job stress, there are also other sources of dissatisfaction in the lawyer’s search for higher needs. These include:

1 Dissatisfaction with lack of guidance and career development within the firm

2 Disenchantment with the firm’s pressure to generate business, bureaucratisation, impersonality and lack of collegiality.

3 Disillusionment with future partnership prospects.

4 Unable to find meaning in legal work.

Lawyers’ personality: perfectionist and pessimist

Interestingly, the lawyer himself may be a source of dissatisfaction. It has been suggested that beyond stress and long work hours, the legal environment gives rise to the lawyer personality of a ‘perfectionist and pessimist’ that renders it difficult to find happiness. Law is inherently a stressful profession with expectations of invariant perfection requiring long hours and a scrupulous eye for detail. The nature of work tends towards pessimism with a congenital absence of spontaneity and exuberance. Law school and the profession also tend to attract success-conscious competitive personalities, thereafter moulding them into highly driven, detail-conscious perfectionists. Some become pessimists stressed out, cynical and living in fear of mistakes.

Lawyers drawn into an unhappy money culture

Another interesting proposition is that an unhappy emphasis on material rewards widespread within the profession is the root of the problem contributing to the competitive long hour culture and dissatisfaction of lawyers. There may be some truth in this proposition. In the Ministry of Law survey, 58 per cent of young lawyers cited ‘remuneration did not commensurate with workload’ as the second most significant reason for leaving practice. This is despite the fact that Singapore lawyers are among the highest paid professionals in Singapore, with a newly-minted lawyer earning 150–200 per cent of the average university graduate’s salary.

There may be two reasons for the money culture of the legal profession. First, the competitive desire of legal professionals to get ahead of their peers is played out in a game where success is measured in monetary terms. Earning and spending money is a way to signal achievement and social status. Ambitious competitive professionals become intensely curious about how much money other professionals (even in other industries) are making. Here, money is more than a means to a living; it is an indicator of success benchmarked against one’s peers.

Second, the competitive culture of the profession fuels a self-perpetuating cycle of long hours and unhappiness that individuals attempt in vain to compensate for monetarily. Such a competitive culture is not uncommon amongst high-achieving professionals, including investment bankers. Within a large law firm of ambitious lawyers, individual competitiveness can translate into a firm culture of long hours inside the office. The high monetary rewards coupled with a lack of time to spend hard-earned money lead to a situation of long hours of toil inside the office and short hours of consumption outside the office. Gruelling schedules compensated by high pay scales are accepted as a means to afford ‘extras’ in which there is little time to enjoy. A substantial income fills the void and the pattern of compensatory consumption becomes self-perpetuating, fuelling empty desires for more material rewards. The seduction of monetary rewards makes it difficult to give up the long hours and stressful lifestyle for more satisfying work conditions.

Push and pull factors

The attrition of lawyers from the legal profession in Singapore is attributable to both push and pull factors. The push factors set the stage for ripe dissatisfaction, with young lawyers increasingly drawn to the pull of more attractive alternatives beyond legal practice in Singapore. Heavy workload, long hours, stress and job dissatisfaction form the major push factors that lead increasing numbers of lawyers to leave practice. This is attributable to the changing priorities of a new generation with higher priority on work-life balance and desire for family and personal time.

Against a festering environment of push factors, there is also the pull and lure of attractive alternatives beyond legal practice in Singapore. There is much interest in working abroad in foreign legal jurisdictions seen to be more professionally and financially enriching. Also, increasing numbers of in-house positions provide a career alternative with possibly better hours, control of work time and the advantage of being a ‘stressor’ client instead of the ‘stressed-out’ lawyer.

Addressing the Problem

National concerns

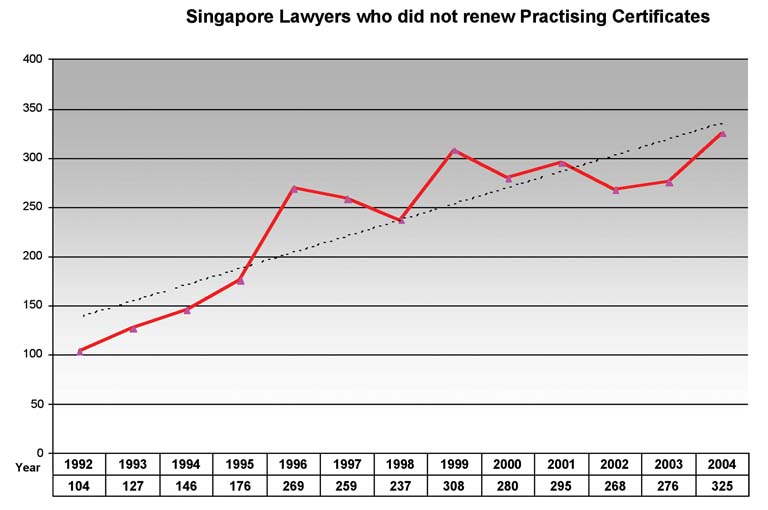

On the national level, the Singapore government and the Law Society are concerned about the dangers of a shrinking Bar. Negative growth and an ageing trend of the Singapore Bar have resulted from the mid-level drain of associates leaving the profession.

The crisis is not only about quantitative numbers, but qualitative implications in a profession that is rapidly drained of its future generation of lawyers. The impact is most keenly felt in the present shortage of senior associates and the impending shortage of experienced lawyers in the future. As older lawyers retire, there will be increasingly fewer younger lawyers left to replace the loss of knowledge and experience within the profession.

Source: Ministry of Law Census of the Legal Industry and Profession 2001

Singapore cannot afford to have a diminished legal services industry. To ensure international economic competitiveness, Singapore needs to expand its pool of legal expertise to support the international and domestic markets for financial, biomedical and other services. To increase the supply of fresh lawyers is not the solution to the attrition problem. The critical issue is to retain and groom experienced young lawyers for the future of the Singapore legal profession. What is at stake is the next generation of the Singapore legal profession.

Business case for change

From the law firms’ perspective, there is a critical business case for change – recruitment, retention, loyalty, commitment, productivity, quality of legal work, and maintaining effective client relationships.

The drain of legal associates greatly impacts the law firm with increased costs of recruitment and retraining. There is lower productivity in the form of reduced quality of legal work, decreased client service and even possible discontinuity of the client relationship. Clients do not get efficient services from bleary, burned-out lawyers. Lawyers who are less stressed can be more dynamic and innovative. Retaining lawyers would improve client service with experienced lawyers better able to understand and serve client needs, facilitating continuity of the client relationship.

In the 21st century, work-life balance policies are a key to a law firm’s competitiveness and long-term profitability. Better retention of staff would improve the firm’s cost effectiveness. Any inconvenience in allowing work schedule flexibility is a lesser problem than losing talented employees and having to find and retrain new people. Law firms that recognise their lawyers’ needs for work-life balance will have a competitive edge in recruiting and retaining talent. An Employer of Choice can attract and retain top-notch lawyers, tapping into the potential manpower pool of experienced lawyers who would like to engage in professional work on a part-time or alternative work arrangement.

Recommendations

This study proposes three broad approaches to address the problem of attrition rising from long work hours and job stress within the legal profession. First, law firms could reduce the stressors to avoid burnout. This can be achieved within possible limits. Second, stressors that cannot be reduced could be better controlled and managed. Third, there is potential to increase the rewards of professional work towards fostering greater job embeddedness.

Recommendation 1: Reduce stressors

Reduce long work hours

Law firms should look into ways to reduce the long hours at work. This is a critical issue, where lawyers have expressed willingness to trade some pay for reduced work hours. In this, more lawyers could be hired so that the heavy workload can be spread out. There is also considerable potential to improve paralegal professional support which today remains underutilised in local law firms.

To address long work hours and the presenteeism culture, it is critical to change the corporate culture in law firms. This requires senior management commitment to dispel the culture of presence by encouraging staff not to stay late and to be examples themselves in not keeping long work hours that add pressure to their subordinates. There needs to be a measure of work performance beyond the visible number of hours worked. To counter any presenteeism culture, it is necessary to change the work patterns and performance management system.

Improve management

Admittedly, many lawyers are not natural managers and there is room for management practices to be improved. First and foremost, it is important for law firm partners to treat employees with trust and respect. In a fast-paced and high-stress environment, it is easy for harried partners to unconsciously vent it upon their junior associates. Besides giving decent treatment to another human being, it is necessary for partners to coach their associates and to motivate performance by giving challenging and rewarding work. It is also critical to secure the loyalty and commitment of their associates by laying out a viable future career development plan.

Recommendation 2: Control stressors

Given the demanding nature of legal professional practice, there is a limit to the reduction of work hours. Where the workload and the hours cannot be further reduced, these stressors could be better controlled and managed.

Improve work distribution

The problem of uneven workload distribution is where certain associates tend to receive more work from partners. Some partners have insufficient associates to divide the heavy workload. In a ‘pool’ system of associates, partners are free to assign work to any associate within the pool. Capable associates are perceived to be capable of taking on more work, and are thus overloaded with work from multiple partners. To address this, management supervision is crucial to ensure that any associate is not overworked. There may be a need for an assigning person to manage associates’ workload. It would be useful to have a system to flag out overworked employees.

Time-off from work

Brief ‘time-outs’ can help employees regroup with the aim of thinking more clearly and even more creatively about work. The firm could provide for sabbaticals and suitable perks such as beach holidays, tickets to the opera or sports events for stressed-out lawyers, and other periodical weekend getaways.

Often, it is the most burned-out lawyers who do not clear their leave entitlement. Firms should allow and encourage lawyers to clear their leave. There is a need to have balance, and to give pockets of time-off for associates to clear leave. In this, partners must be committed to avoid associates’ burn-out.

Better quality hours

Given the professional demands of practice life for lawyers, there may be a limited extent of effective measures to reduce the stressors at work. In such a case, if the long hours and stress cannot be further reduced, then we must examine the scope for not only better quantity, but better quality and choice of work hours.

The problem is not always the actual number of hours worked per se. What matters most is the subjective meaning of the work hours – the required trade-offs, the quality of experience on the job, and the fit between the employees’ schedule preferences, priorities and the number of hours worked.

Lawyers with effective control over their work would be better able to cope with work stress conditions. In this, better work arrangements such as flexible hours, working from home, job sharing, part-time contract work, family leave policies and flexible working schedules would be steps in the right direction.

Accommodate personal/family needs

Firms need to undergo a mindset shift towards part-time and flexible work arrangements. Such schemes are not about losing people, but gaining new work resources by tapping into a pool of people previously not utilised. The existence of family-friendly parental leave schemes would be less expensive than recruiting and training replacements. For the law firm, part-time staff may give the firm more flexibility to deal with fluctuating business cycles and staffing needs. Firms can align capacity with demand at times when the economy is soft. Retaining lawyers would also mean retaining clients who prefer to work with a part-time lawyer with whom they have had an existing relationship, than a brand new full-time lawyer.

A lawyer may be on part-time work hours, but still provide full-time commitment to clients – being reachable at home, with convenient fax machine and computer access. For lawyers with other fixed responsibilities, having periods of time away from work each week in the form of reduced work hours can have beneficial effects on work quality, satisfaction and retention. These are major tools to help firms win the war for talent amidst a shrinking profession.

Feedback

It is important to make feedback a part of the organisational culture. Unknown to management, there may be significant discrepancy between how law firm managers view their firms and what associates in those same firms experience as their reality. There also needs to be a credible grievance mechanism.

Recommendation 3: Increase rewards

Higher salaries are not the answer

Besides reducing and controlling the push factors of dissatisfaction, another approach is to address the effort-reward imbalance by increasing the rewards and pull factors to compensate for the long hours and stress at work. In this, the first and primary response of Singapore firms has been to raise the salaries of young lawyers. The reality is that higher salary alone is not enough. Money used as compensation to justify working long hours spurs a cycle of insatiable material wants. The positive effects of more pay are often short-lived. Retention cannot be accomplished purely through money. The more important factors for job fulfilment relates to recognition, appreciation and a sense of achievement and professional accomplishment.

Create job embeddedness

The key is to create job embeddedness. Law firms need to increase the number of connections and strength of attachments of the lawyer with the firm – to create a web-like quality of embeddedness to keep people on the job. There are three factors of ‘job embeddedness’:

1 links – collegial relationships and connections between people;

2 fit – employee’s perceived compatibility with the job, organisation and community; and

3 sacrifice – making individuals unwilling to sacrifice or give up perks, routines or projects to which they have grown accustomed.

Instil a professional calling

Instilling a professional calling in lawyers would also bring about greater meaning and satisfaction in legal work. This could be done through pro bono schemes, role models, mentors, and even a ‘find-your-niche’ programme to help young lawyers discover their interest and professional calling.

Conclusion

The attrition problem arises from long hours and stress faced in particular by young lawyers in Singapore. To ameliorate the workload and stress inherent within the profession, law firms should look into improving management and human resource practices to give lawyers better control of their time and workload.

In an industry that faces a shortage and mid-level drain of young lawyers, a law firm would gain the competitive advantage if it is able to restructure the work and careers of its associates to meet both the firm’s needs and their personal priorities. Management support is critical to ensure the success of work-life programmes introduced to improve the work-life balance of lawyers.

Besides the law firms, the Law Society could be a catalyst to facilitate change. To incentivise change, the government and the Law Society could conduct an annual survey to rank law firms according to various management organisational measures, including work practices and employee satisfaction. This enables an objective ranking of firms’ employee-friendly work practices that can be publicised to law students and other lawyers seeking a change of environment and firm culture. The marketplace will then determine which firms win the war for talent.

Samuel Ang

E-mail: [email protected]