This article discusses recent developments in Court ADR for civil matters, and the recently issued Registrar’s Circular No 3 of 2011 which introduces Neutral Evaluation as an additional ADR option.

Finding the Appropriate Mode of Dispute Resolution: Introducing Neutral Evaluation in the Subordinate Courts

Introduction

The Alternative Dispute Resolution (“ADR”) movement has gained significant traction over the last three decades and has been expanding at a rapid pace in many common law jurisdictions. The allure of ADR lies, in large part, in its recognition of litigants’ desire for self-determination and autonomy in resolving their disputes. ADR became even more attractive as dissatisfaction with the traditional Court system grew. In the seminal Roscoe Pound Conference on Popular Causes of Dissatisfaction with the Administration of Justice in USA, the changing role of the Courts was highlighted, casting ADR further into the spotlight.1 Instead of offering only adjudication in a conventional trial setting, the Courts were envisaged as a “multidoor courthouse” – a comprehensive justice centre in which cases are screened and referred to the most effective dispute resolution process.2 This philosophy for the administration of justice has since been embraced by many judiciaries, including Singapore. Both litigation and ADR are now crucial components of the dispute resolution framework of many jurisdictions, with each serving its own distinct functions. The role of the lawyer has accordingly been recast in light of this reality – the lawyer, faced with the convergence of the cultures of litigation and consensus-building, will now have to adopt a “more nuanced, multi-pronged strategic approach to both fighting and settling”.3

In tandem with the changing dispute resolution landscape, the Subordinate Courts have, since 1994, offered ADR for civil disputes through its Primary Dispute Resolution Centre.4 This article provides an overview of the key developments in Court ADR in the context of civil matters commenced before the Subordinate Courts, including the recently issued Registrar’s Circular No 3 of 2011 which introduces Neutral Evaluation as an additional ADR option. The concept of Neutral Evaluation and when it is suitable will also be explained below.

Modes of Dispute Resolution for Civil Disputes

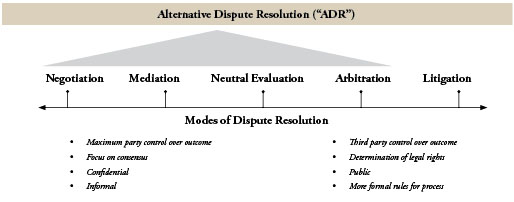

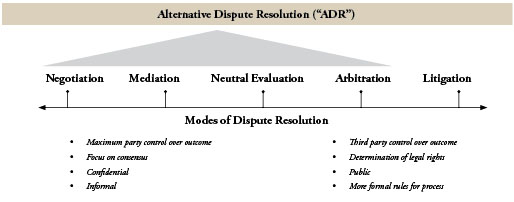

There is a variety of modes of conflict resolution that can be utilised for any civil dispute. Litigation has been the traditional mode of dispute resolution before the Courts. Occupying the extreme right end of the conflict resolution spectrum, litigation involves the parties relinquishing their control over the outcome to a neutral, the Judge. The primary aim of litigation is to achieve a determination of the parties’ legal rights. It is also the most formal process, requiring adherence to substantive and procedural law.

The modes of dispute resolution apart from litigation have been traditionally termed Alternative Dispute Resolution or ADR processes, being processes that are external to the Court system. At the extreme left end of the spectrum is negotiation, which does not involve any third party intervention. The parties retain the most control over the outcome; their consensus alone is required to resolve their dispute.

The other three modes – mediation, neutral evaluation and arbitration – entail differing extents of third party intervention. Of these modes, mediation is the least intrusive into the parties’ autonomy. The mediator merely facilitates the conversation between the disputing parties with the goal of assisting them in reaching a consensus. The focus of mediation is also not on determining legal rights, but on understanding each party’s ultimate concerns and helping parties arrive at a solution that meets these concerns. Mediation has proven to be the most popular ADR method largely because of its association with party autonomy.

By contrast, both neutral evaluation and arbitration, like litigation, focus on the determination of legal rights. In arbitration, a private individual – the arbitrator – performs the role of a Judge, making a decision that binds the parties.5

Neutral Evaluation

Neutral Evaluation involves a third party neutral giving the parties a non-binding assessment of the case at an early stage on the basis of brief presentations made by the parties. Unlike mediation, in which the mediator assists the parties in reaching an agreement without necessarily stating an opinion on the case, the explicit aim of Neutral Evaluation is to provide a without-prejudice evaluation of the strengths and weaknesses of a case. Faced with an independent assessment of the merits of the case, and a better understanding of their prospects of success at trial, the parties are more likely to settle their dispute.

Neutral Evaluation was first pioneered in the Northern Californian Courts in the 1980s. Extensive studies showing the benefits of this mode of ADR have led to many other jurisdictions replicating it. While mediation remains the more popular ADR mode in most jurisdictions, Neutral Evaluation has been shown to be particularly beneficial in the following ways:

1. Encourages the parties to confront their positions systematically at an early stage and seriously consider the wisdom of early settlement

Litigants often fail to confront their and their opponent’s positions systematically early in the pre-trial stages. The assessment delivered by the neutral apprises the parties of the relative strengths and weaknesses of their case, and may encourage parties to seriously consider the prospects of an early settlement.

2. Allows litigants “their day in Court” and reduces their sense of alienation

Litigants may feel alienated from the litigation process because of the formalities associated with the pre-trial and trial processes. Neutral Evaluation is almost equivalent to a trial because it is structured as an adjudicatory process, except that formal rules of evidence do not apply, and the process is fully confidential, non-binding and shorter. When the litigants are directly involved in this adjudicatory process, their desire for their “day in Court” is satisfied, and their understanding of the issues in the dispute is also improved.

3. Maximises face-to-face interaction between the parties

In Neutral Evaluation, the parties are almost always in a group session in one another’s presence. During the group sessions, each party presents the merits of the claim or defence, and the experts would also present their views. The parties have the opportunity to ask questions and respond to queries, as well as observe their opponents. Neutral Evaluation is particularly beneficial when it is important for a litigant to observe the other side’s presentation before being more confident or comfortable about his or her decision to proceed. Conversely, it would also be helpful for the litigant to personally see the opponent’s presentation, observe the witnesses giving testimony and assess how persuasive the expert witness is, before being convinced about the strengths of the opponent’s case.

4. Provides a reality check for unrealistic litigants

Most litigants embroiled in disputes would profess to be confident about their prospects of success at trial. This confidence, whether justified or misplaced, is frequently a barrier to settlement as each party feels strongly that there is no room for negotiation. When a litigant is being unrealistic about the merits of his case, Neutral Evaluation is useful in providing a “second opinion” and a reality check. The litigant may then modify his or her expectations accordingly, and be more prepared to negotiate a settlement.

5. Narrowing of issues

Even where Neutral Evaluation does not lead to a settlement, it may help parties clarify or narrow issues, increase communication across party lines, and consequently increase the likelihood of success of subsequent settlement discussions.

6. Cost savings

Since Neutral Evaluation is a summary process in which formal evidential rules do not apply, it will be shorter than a trial. Legal costs and costs in paying for expert witnesses’ time will be less in Neutral Evaluation than at a trial. Further, where a case involves expert witnesses, it is possible to use video conferencing to reduce the cost of having an expert present at Neutral Evaluation.6

Neutral Evaluation and Other ADR Processes in the Primary Dispute Resolution Centre

The Primary Dispute Resolution Centre (“PDRC”) currently offers ADR services for all civil matters, pursuant to O 34A of the Rules of Court. Different ADR processes are offered for the following categories of cases:

1. Non-Injury Motor Accident (“NIMA”) cases with claim exceeding $3,000

Pursuant to para 151 of the Subordinate Courts’ Practice Directions, all NIMA claims exceeding $3,000 are dealt with in the PDRC as a matter of course. Parties would receive a notification from PDRC to attend “Court Dispute Resolution” approximately eight weeks after appearance has been entered in a NIMA suit. NIMA claims below $3,000 are to be adjudicated in the Financial Industry Disputes Resolution Centre, or FIDReC.

The process used for NIMA cases is a shortened version of Neutral Evaluation. Only the solicitors, and not the clients and other witnesses, would be present at this session. Based on documents and evidence adduced by the solicitors, the Settlement Judge in PDRC would give an indication of the likely outcome of the matter at trial. The parties could then use the indication as a basis to negotiate a settlement.

2. Personal Injury (“PI”) Matters

Since May 2011, all personal injury matters have been referred to PDRC as a matter of course pursuant to para 151C of the Subordinate Courts’ Practice Directions. These matters include motor accident cases involving injury, and industrial accident cases. As with NIMA cases, these cases are dealt with through a summary neutral evaluation process. Indications on liability and quantum of the dispute are given to facilitate settlement negotiations.7

3. Other general civil matters

In all other civil matters, the parties may currently indicate their preferences as to the ADR process they wish to pursue in the ADR Form (Form 6A in the Practice Directions) which has to be filed by all parties together with the Summons for Directions (“SFD”) application. Parties currently have the option of choosing between mediation in the PDRC, or arbitration offered by the Law Society Arbitration Scheme.8 Where both parties are agreeable on an ADR process, the Deputy Registrar presiding over the SFD would refer them to the appropriate process.9

Mediation has been a popular mode of dispute resolution chosen by the parties. The mediator in PDRC would either be a Settlement Judge or an Associate Mediator of the PDRC. The latter is a mediator who is also legally qualified, and who has been jointly trained and accredited by PDRC and the Singapore Mediation Centre.

Introducing Neutral Evaluation as Another ADR Option at the SFD Stage

Under the recently issued Registrar’s Circular No 3 of 2011, the Subordinate Courts have commenced a pilot project to introduce Neutral Evaluation as a further ADR option for general civil cases falling under category “3” above. For a six-month period commencing on and from 17 October 2011, a Deputy Registrar hearing a SFD application may, with the parties’ consent, refer suitable civil cases falling under category “3” above for Neutral Evaluation. The Neutral Evaluation proceedings are more elaborate than the existing ADR services offered by the PDRC in respect of NIMA and PI cases, and involve a more detailed consideration of the legal arguments and evidence relied upon by the parties. NIMA and PI cases will not be covered by the pilot project and will continue to be dealt with in accordance with the existing ADR processes set out in paras 151 and 151C of the Subordinate Courts’ Practice Directions. As this is a pilot scheme, the ADR Form has yet to be amended to formally introduce this new process. Instead, the Subordinate Courts will refer suitable cases to Neutral Evaluation on a case by case basis, and review the cases that have used this process. The Subordinate Courts will consider formally including this option in the ADR Form if the pilot programme yields positive results.

How Would Neutral Evaluation Work?

Neutral Evaluation will involve a Settlement Judge (the “Evaluator”) giving an assessment of the merits of the claim after hearing presentations from all the parties (an “evaluation”). This process has the following notable features:

1. Non-binding (unless parties elect for binding evaluations)

The default position is that evaluations would be non-binding. However, parties may elect in advance of the Neutral Evaluation hearing for the Evaluation to be binding. Where such an election is made, parties are required to agree and undertake in advance that a consent judgment would be entered or terms of settlement would be recorded to reflect the outcome of the Evaluation.

2. Confidential

As in any ADR process, the opening statements submitted by the parties, the Neutral Evaluation proceedings, and the evaluation delivered by the Evaluator will remain confidential and will not be disclosed to the trial Judge if the matter proceeds to trial.

3. Who attends

The solicitors, clients and key witnesses (including expert witnesses) should attend the Neutral Evaluation hearing and make brief presentations of the arguments or evidence (as the case may be) to the Evaluator. The clients would have the opportunity to participate in the presentation.

4. Dealing with expert testimony: Single Joint Expert or Witness Conferencing

Neutral Evaluation offers a cost-effective way of analysing expert testimony, and is particularly useful for cases which turn on technical evidence. The parties will be encouraged prior to the Neutral Evaluation to agree on a single joint expert. Alternatively, where each party would prefer to use his own expert witness, the Evaluator would assess the experts’ testimony through a process called witness conferencing (which is also known as “hot tubbing”), which is further elaborated below.

Once the parties are referred for Neutral Evaluation, the following process would take place:

1. A Preliminary Conference would be scheduled between a PDRC settlement Judge, the lawyers, and the parties approximately 21 days after the case is referred for Neutral Evaluation to discuss all matters that would facilitate a quick and economical conduct of the neutral evaluation hearing. At the conference, the Neutral Evaluation date would be fixed and details for preparation for the Neutral Evaluation would be discussed. In general, Neutral Evaluations will be fixed for a half-day session.

2. Submission of Opening Statements by the parties no later than two working days before the Neutral Evaluation hearing date.

3. The Neutral Evaluation hearing

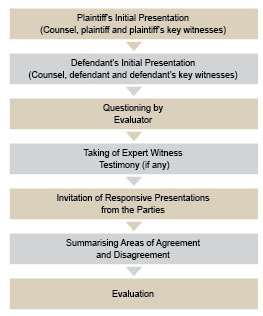

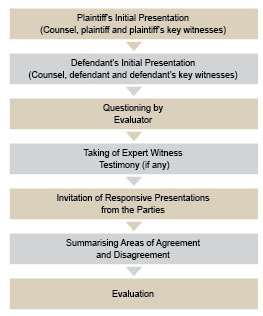

At the Neutral Evaluation hearing, the parties and their solicitors will present their case and the available supporting evidence to one another and the Evaluator. Key witnesses on each side will also be called to give testimony for this purpose. Rules of evidence do not apply in this process, and cross-examination will generally not take place. Where separate expert witnesses are called, they would give evidence using the expert witness conferencing approach set out below. The Evaluator may at any time during the Neutral Evaluation hearing ask questions to probe or clarify any submission or evidence presented by the parties and their witnesses. Where appropriate, the Evaluator would also identify areas of agreement or disagreement. The parties would also be given the opportunity to make any responsive presentations. After all presentations and evidence have been made or delivered, the Evaluator will deliver an oral assessment of the merits of the parties’ case. The process is summed up below diagrammatically:10

4. If no settlement is reached at the end of the Neutral Evaluation, the settlement Judge would help the parties develop an efficient case management plan. This would include further mediation or giving directions for trial.

When Would a Case be Suitable for Neutral Evaluation?

A dispute may particularly benefit from a Neutral Evaluation if it is one:

1. that turns primarily on documentary evidence eg, construction claims;

2. that turns on conflicting expert evidence, and where it might be costly and time-consuming for expert witnesses to testify at length in a trial;

3. where parties are uncertain about the merits of their case and are keen to have a neutral person with subject matter expertise assess the merits of their case;

4. where parties are of the view that they have strong cases and are, therefore, unwilling to explore settlement. In such cases, a reality check by a neutral evaluator might be useful;

5. that hinges on technical issues that have to be resolved before the parties would be in the frame of mind to negotiate. Examples of such cases could include: (i) construction or renovation contract cases, in which there are disputes on whether work was carried out in accordance with the agreed specifications, and where parties may not be prepared to discuss payment issues before such issues are resolved; and (ii) medical negligence cases, in which parties may wish to seek a determination on whether there was negligence on the facts before negotiating on how to achieve an overall resolution of the dispute.

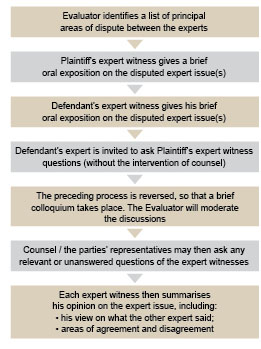

A Note on Witness Conferencing

Witness Conferencing, or “hot tubbing” is a witness examination technique that is commonly resorted to in international arbitration proceedings, and which has further been institutionalised in civil trial proceedings in a number of jurisdictions such as Australia. As its name implies, this evidentiary process involves the simultaneous hearing of all expert witnesses in the form of a panel discussion led by the third party neutral. Unlike the traditional mode of witness hearing where witnesses are examined and cross-examined sequentially, this process is interactive in nature, and is intended to allow any areas of disagreement in opinions between the experts to be discussed or clarified in a joint conference between the experts. It is more efficient than the traditional mode of witness hearing, as all experts who have knowledge on a common issue are brought together to collectively provide their opinions. Specific points of disagreement can be easily highlighted and addressed in a joint conference between the experts. The total time required to hear all the expert witnesses would be less than under the traditional method of examining and cross-examining each witness in turn. It has also been observed that witness conferencing is useful in bringing out the real facts. As each expert acts as a natural check or counterbalance to the other, “it is extremely difficult for a witness under the gaze of his counterparts to persist in a clearly inaccurate version of facts”.11

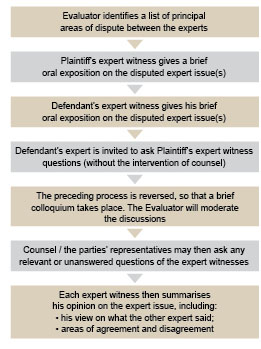

Witness conferencing will be utilised in Neutral Evaluation to assess expert testimony. A suggested procedure for this method is set out below. Each party’s expert witness would be given the opportunity to question and clarify any views expressed by the other expert. Each witness would then at the end of the process summarise his opinion on the expert issue, including any areas of agreement or disagreement between the views proffered by the respective experts.

*At any time during the Witness Conferencing process, the Evaluator may intervene and ask questions to probe or clarify.

Conclusion

Neutral Evaluation is but one of a variety of dispute resolution options offered by the Subordinate Courts to litigants. Solicitors play a central role in advising and assisting their clients to choose the most appropriate mode that would suit their specific needs and further their interests. For more information on this new process, please refer to the Subordinate Courts’ website at http://www.subcourts.gov.sg, under “Quick Links – Court Dispute Resolution”.

► District Judge Dorcas Quek

District Judge Seah Chi-Ling

Primary Dispute Resolution Centre, Subordinate Courts

Notes

1 See Carrie Menkel Meadow “Roots and Inspirations: A Brief History of the Foundations of Dispute Resolution” in Handbook of Dispute Resolution (Michael L. Moffitt & Robert C Bordone eds, 2005) at p 20.

2 See Frank Sander, Varieties of Dispute Resolution 70 FRD III (1976) and A. Levin & R. Wheeler The Pound Conference: Perspectives on Justice in the Future (West Group, 1979).

3 Julie Macfarlane, The New Lawyer: How Settlement Is Transforming the Practice of Law (University of Washington Press 2008), at 109.

4 The Subordinate Courts also offer ADR for other types of disputes, including family disputes, minor criminal offences and the Small Claims Tribunals. More information may be found on the Subordinate Courts’ website at http://www.subcourts.gov.sg.

5 Goldberg, Sander, Rogers and Cole, Dispute Resolution: Negotiation, Mediation and Other Processes, (Aspen Publishers, 5th Ed, 2007)at 318; Laurence Boulle & Teh Hwee Hwee, Mediation: Principles Process Practice (Butterworths Asia, 2000) at 72-73.

6 W.D. Brazil, “Early Neutral Evaluation or Mediation? When Might ENE Deliver More Value”, Volume 14 Dispute Resolution Magazine No. 1 (“ABA” section of Dispute Resolution, Fall 2007).

7 Note that indications on quantum will be given for all industrial accidents. For motor accident claims involving injury, the solicitors may opt to ask for an indication on quantum. See para 151C of the Practice Directions, at http://www.subcourts.gov.sg, under “Legislation and Directions”.

8 Information on the Law Society Arbitration Scheme may be found at http://www.lawsociety.org.sg/lsas.

9 For more information about the ADR Form, please refer to an earlier article published in the Law Gazette, “The ADR Form in the Subordinate Courts – Finding the APPROPRIATE mode of Dispute Resolution”, available at http://www.subcourts.gov.sg, under “Quick Links – Court Dispute Resolution”.

10 Adapted with permission from W.D. Brazil, Early Neutral Evaluation in the Northern District of California – Handbook for Evaluators (2008, Rev Ed).

11 P. Wolfgang, “Witness Conferencing Revisited”, 2004 Reports of the International Colloquium of CEPANI at 156-171. See also Michael Hwang, “Witness Conferencing” in The 2008 Legal Media Group Guide to the World’s Leading Experts in Commercial Arbitration, p 3 (James McKay, ed 2008) by Mr. Michael Hwang, SC (Singapore), available online at http://www.arbitration-icca.org/media/0/12232964943740/witness_conferencing.pdf.