This article examines the ethical limits of making imputations against complainants of sexual offences in light of three recent Singapore Court decisions. It also discusses the potential scope of reform of these ethical duties.

I. Introduction

“What did your father see in the window, the crime of rape or the best defense to it? Why don’t you tell the truth, child, didn’t Bob Ewell beat you up?”

— Cross-examination of Mayella Violet Ewell by

Atticus Finch in Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird1

Three recent Singapore Court decisions have cast the spotlight on the ethical duties of defence counsel who make imputations2 against complainants of sexual offences at two crucial stages of criminal proceedings: cross-examination and submissions on sentence.

Although defence counsel have a duty to present and advance their client’s best case to the Court, lawyers’ professional ethics recognise that ethical parameters are necessary to ensure that they do not make imputations that are only intended to humiliate or abuse a complainant of a sexual offence. Such unethical imputations are not only inconsistent with a lawyer’s standing as a member of an honourable profession, but also undermine the dignity of the complainant and the integrity of the criminal proceedings.

Part II of this article provides a brief summary of the three decisions and examines a key ethical theme that arises from each decision on making imputations against complainants of sexual offences. Part III develops on the ethical themes identified in Part II by exploring two deeper underlying ethical concerns: the need for coherence in the ethical rules governing the making of imputations and the use of stereotypical imputations. Part IV advocates reforming the existing ethical framework in view of broader considerations, but also sets out a few arguments for preserving the status quo.

II. The Three Decisions and Their Ethical Themes

Ethical Limits Rest Primarily with the Lawyer, not the Court

The well-publicised decision of Public Prosecutor v Xu Jiadong3 (“Xu Jiadong”) concerned an incident of outrage of modesty by a 22-year old male Chinese national that occurred at night on board an MRT train. The accused was convicted of the charge under s 354(1) of the Penal Code of brushing his forearm against the victim’s lower breasts and sentenced to five months’ imprisonment.

In the Judge’s grounds of decision, he observed, among other things, that the defence counsel had conducted the cross-examination, contrary to ss 153 and 154 of the Evidence Act, in an “indecent and scandalous” manner by focusing on the “victim’s attractiveness” or at least in a way which was “intended to insult or annoy the victim”.4 Even if the cross-examination had been properly conducted, the judge noted that the defence counsel’s focus on, inter alia, the victim’s “breast size” was “needlessly offensive in form”.5

The Judge also commented that the defence counsel’s cross-examination had caused the victim to “re-live her odious experience” and to be “visibly affected” even after the proceedings were stopped at one point.6 The Judge concluded that the defence counsel’s conduct was “completely unacceptable” and was “plainly not in keeping with – and fell far short of – the best traditions of the Singapore Bar”.7

Xu Jiadong was primarily concerned with the Court’s power under ss 153 and 154 of the Evidence Act. The Judge noted that these sections are “encapsulated”8 in rule 12(5) of the Legal Profession (Professional Conduct) Rules 2015 (“PCR 2015”):

A legal practitioner must not make any statement, or ask any question, which is scandalous, is intended or calculated to vilify, insult or annoy a witness or any other person, or is otherwise an abuse of the function of the legal practitioner. [emphasis added]

One key ethical theme that arises from Xu Jiadong is that although the Court has the power under the Evidence Act to forbid the making of questionable imputations, the defence counsel, and not the Court, is primarily responsible for observing the ethical limits of making imputations during cross-examination. As noted in Xu Jiadong:

Finally, members of the Bar need to observe high standards of professional conduct and a proper sense of responsibility in the conduct of cases; if this is not done, the whole profession will suffer in the public’s estimation: Croll v McRae (1930) 30 SR(NSW) 137 at 146 per the Chief Justice of New South Wales, Australia. Counsel’s duty to conduct himself honourably is not lessened by the existence of the Court’s power to forbid improper or offensive questions: James Lindsay Glissan in Cross-Examination: Practice and Procedure (Second Edition, Butterworths, 1991) at 175.9 [emphasis added]

In his classic tome The Art of Cross-Examination,10 Francis L Wellman (“Wellman”) explained why the Judge cannot be the key ethical gate-keeper in the making of imputations:

A judge, however, to whose discretion such questions are addressed in the first instance, can have but an imperfect knowledge of either side of the case before him. He cannot always be sure, without hearing all the facts, whether the question asked would or would not tend to develop the truth rather than simply degrade the witness. Then, again, the mischief is often done by the mere asking of the question, even if the judge directs the witness not to answer. The insinuation has been made publicly – the dirt has been thrown. The discretion must therefore, after all, be largely left to the lawyer itself. He is bound in honor, and out of respect to his profession, to consider whether the question ought in conscience to be asked – whether in his own honest judgment it renders the witness unworthy of belief under oath – before he allows himself to ask it.11 [emphasis added]

The Ethical Distinction between an Alleged Victim and a Victim of a Sexual Offence

Public Prosecutor v Ong Jack Hong (“Ong Jack Hong”)12 concerned the offence of sexual penetration of a minor under s 376A(1)(a) of the Penal Code. The accused, who was 17 years old at the time of committing the offence, was convicted and sentenced to a term of 24 months’ split probation. On appeal by the Prosecution, Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon, sitting in the High Court, imposed a sentence of reformative training instead, in view of the need for deterrence and the accused’s antecedents (although unrelated to the offence).

In her submissions on sentence, the defence counsel suggested that because the victim had had sexual relations with her boyfriend, she “had not been traumatised by the incident”.13 The Chief Justice observed that such a conclusion could not “fairly be drawn in all the circumstances” because there was no basis for comparing the victim’s reaction to her sexual encounters with her boyfriend with an encounter that took place with the accused, a stranger, when she was “drunk and vulnerable”.14 In any case, even if the victim had not been traumatised, it would, at best, not be an aggravating factor, but could not be a mitigating factor.15

The Chief Justice also noted that the defence counsel’s submission, which was “directed at the morality of the victim”, was unnecessary as it was “seldom helpful in the context of sexual offences”.16 He reminded legal practitioners that:

[a]s officers of the court, counsel should always be mindful of the importance of ensuring the appropriateness and relevance of any submission that he or she is making, and this is especially so where such a submission impugns the character or integrity of a person who is not only not on trial but is in fact the victim of the crime in question.17 [emphasis added]

The Chief Justice’s observations highlight an important change in the position of a complainant of a sexual offence during the sentencing process. Where the accused has pleaded guilty or has been convicted after trial, the complainant is no longer an alleged victim, but an actual victim. Imputations made against the victim, especially if they are directed at the victim’s character or conduct, must therefore be even further circumscribed since the accused’s culpability is no longer at issue.

The Accused’s Interest May be Harmed by the Imputation

Ng Jun Xian v Public Prosecutor (“Ng Jun Xian”)18 illustrates that it may not always be in the interests of the accused to make imputations against the victim of a sexual offence. This case involved, amongst other charges, a “serious, violent and prolonged” offence of sexual assault of an adult victim in a hotel room. The victim was a foreign national who had entered Singapore on a social visit pass. The accused was sentenced to seven years’ imprisonment and three strokes of the cane for the sexual assault charge under s 376(2)(a) of the Penal Code. On appeal by the Prosecution, the High Court enhanced that sentence to eight years’ imprisonment and six strokes of the cane.

In his submissions on sentence, the defence counsel suggested that the victim was partly responsible for the sexual assault as she had agreed to meet the accused at a club in the early hours of the morning based on their friendship and had given “mixed signals” to the accused by agreeing to accompany him to the hotel.19 It was also suggested that the victim was a hostess working at the club, and not an ordinary tourist.20

The High Court observed that the defence counsel’s suggestions tried to shift the accused’s culpability partly to the victim as they were “obvious insinuations that the victim was a woman of questionable morals who had somehow led the offender on and caused him to think that she liked him”.21 More importantly, they were “factually inaccurate and hence without basis”, as they were inconsistent with the position in the Statement of Facts that the accused had admitted to.22 The High Court noted they were not mitigating factors and that:

it was singularly unhelpful and unnecessary for the offender and his counsel to portray what were ironically termed by them as “objective facts” in a selective and misleading manner before making a vague assertion that “there [were] questions which [could not] be answered”.23

Reiterating the Chief Justice’s reminder in Ong Jack Hong, the High Court emphasised that counsel should “refrain from making baseless submissions that disparage the character, integrity or morality of a victim in an attempt to shift blame to the latter”.24 The High Court added that “such submissions will often be a disservice to the accused, especially one who had pleaded guilty and accepted that he has committed an offence, because they invariably reflect a startling lack of remorse and insight into his behaviour”.25

In the author’s view, Ng Jun Xian has turned a common argument that the client’s interests must be pursued at all costs on its head. Baseless imputations against the victim may in fact weigh against the accused in the Court’s determination of the appropriate sentence. Such imputations may also call into question whether defence counsel had properly acted in the interests of his client.

III. Deeper Ethical Concerns Underlying the Making of Imputations

A closer scrutiny of the ethical themes identified in Part II reveals two deeper ethical concerns underlying the making of imputations. Firstly, given that defence counsel is primarily responsible for observing the ethical limits of making imputations, it is necessary to examine the precise scope of such limits and assess whether they are sufficiently coherent. Secondly, as a conviction of a sexual offence typically has serious consequences, the need to act in the accused’s interests unfortunately attracts the use of stereotypical imputations against the complainant, whether as an alleged or actual victim.

The Need for Coherence in the Ethical Limits of Making Imputations

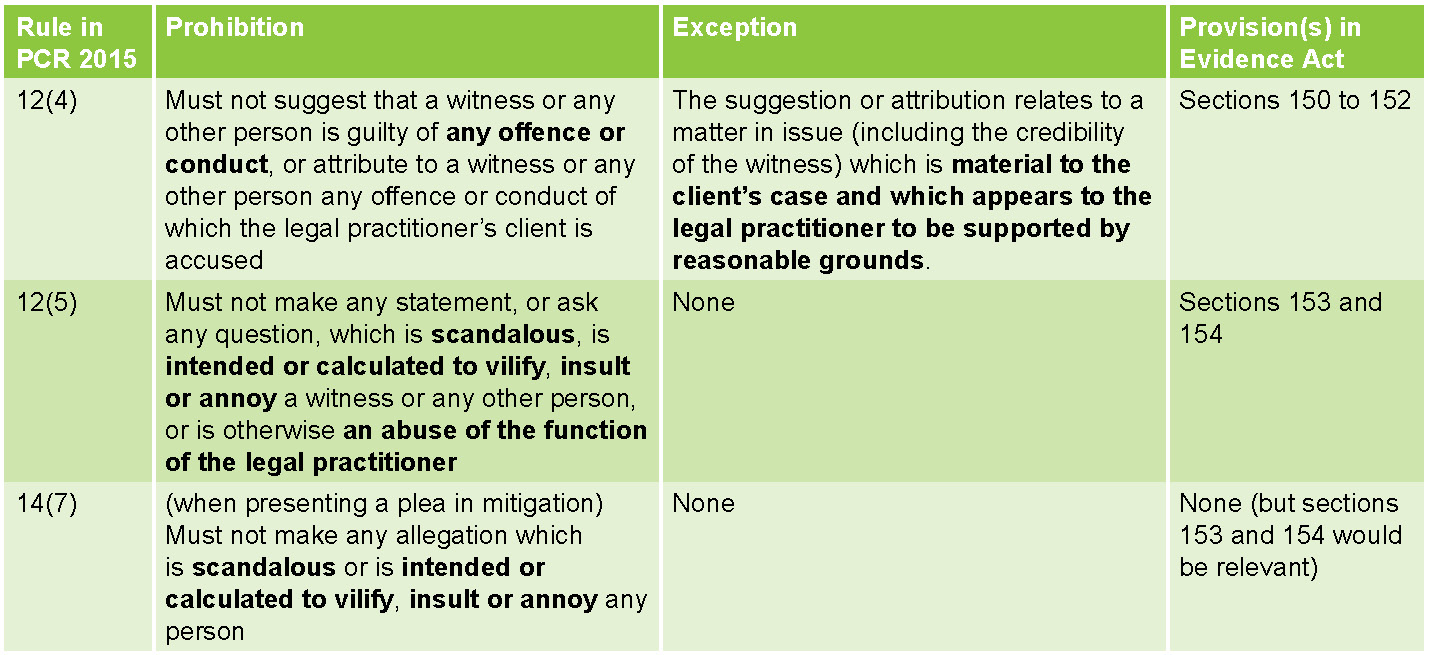

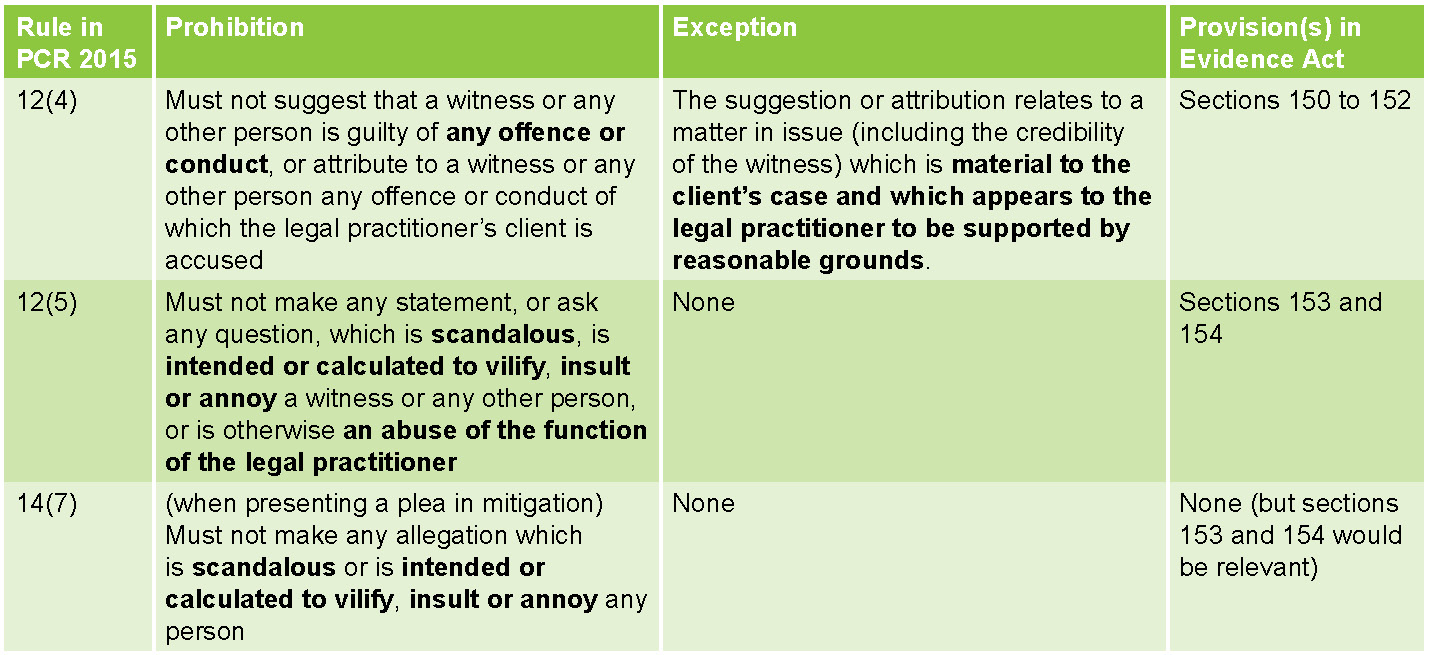

The ethical framework governing the making of imputations in criminal proceedings is complex, as the applicable rules in the PCR 2015 are inextricably linked to the relevant provisions of the Evidence Act pertaining to cross-examination. For the purposes of this analysis, three specific ethical rules in the PCR 2015 relating to imputations will be examined: rules 12(4), 12(5) and 14(7). Rule 14(7) applies only to criminal proceedings, while rules 12(4) and 12(5) apply to all types of Court proceedings.

The table below illustrates this relationship.

The scope of and rationale for each rule are examined as follows.

Rule 12(4)

Rule 12(4) reflects the position under ss 150 and 151 of the Evidence Act that a legal practitioner may ask a question that does not relate to a relevant matter in the suit or proceeding, but “affects the credit of the witness by injuring his character”, if he has “reasonable grounds” to do so. If no such grounds exist, the Court may trigger the disciplinary process under s 152 of the Evidence Act.

The objective underlying s 152, and in turn rule 12(4), is “to balance two competing concerns: the relevance of the witness’s character to his credibility and the right of the witness to be treated with dignity, such that the private aspects of his life not pertinent to his credibility are not pried into”.26 In the context of criminal proceedings, rule 12(4) is also reinforced by rule 14(2) of the PCR 2015, which requires a defence counsel to “pursue every reasonable defence, and raise every favourable factor, on behalf of the accused person in accordance with law” [emphasis added].

Rule 12(5)

As noted above, rule 12(5) reflects the position under ss 153 and 154 of the Evidence Act. Section 153 does not outlaw all “indecent or scandalous” questions, but only those which may have “some bearing on the questions before the court”, but do not “relate to facts in issue or to matters necessary to be known in order to determine whether or not the facts in issue existed”. In other words, evidence that is “essential to the determination of the case is not shut out even if the question asked is scandalous”.27 In the author’s view, rule 12(5), however, appears to impose a higher ethical standard by requiring no scandalous questions to be asked at all.

On the other hand, s 154 does not give the Court any discretion in prohibiting questions that are intended to insult or annoy.28 As such, there should also be no leeway for a defence counsel to ask any question that is intended to insult or annoy, as the rule “lies at the core of an advocate and solicitor’s duty to uphold the integrity of the profession and to conduct himself with dignity and restraint”.29 Even if the question is not intended to insult or annoy, the Court must forbid the question if it appears to be “needlessly offensive in form”, which, in the author’s view, is likely to amount to “an abuse of the function of the legal practitioner” under rule 12(5).

Rule 14(7)

Although rule 14(7) is concerned with imputations made in a plea of mitigation, and not in cross-examination, ss 153 and 154 of the Evidence Act would be relevant given that it shares common wording with rule 12(5).

A few subtle points are worth noting on the interplay among the three rules. Firstly, the language of rules 12(4) and (5) (“suggest”, “attribute”, “make any statement”) indicate that the ethical obligations are not limited to cross-examination, but quite possibly extend to all stages of the criminal trial, such as the opening address, closing submissions or a Newton hearing. Secondly, rule 14(7), unlike rule 12(5), does not use the catch-all phrase “or is otherwise an abuse of the function of the legal practitioner”. It is difficult to find a principled reason for this distinction.

Thirdly, it is uncertain whether the prohibition in rule 12(5) applies if the imputation is material and is supported by reasonable grounds under rule 12(4). Local academic commentary seems to suggest that rule 12(4) takes precedence,30 which is consistent with the interpretation of s 153 of the Evidence Act above and the right of defence counsel not only “to test [the witness’s] accuracy, veracity or credibility”,31 but also “to shake his credit by injuring his character”.32

However, rule 12(5) is not expressly made subject to rule 12(4) and even if “scandalous” questions are permitted where they are relevant to the case, the same reasoning does not apply to questions that are “intended to insult or annoy” or are “needlessly offensive in form” as s 154 of the Evidence Act does not provide for any exception. This uncertainty may also have implications for civil proceedings and similar concerns would apply in considering whether rule 14(7) is impliedly subject to rule 12(4).

The second and third points discussed above suggest that the existing ethical framework is not entirely coherent, although the efficacy of each rule is not in doubt.

The Use of Stereotypical Imputations

Another deeper ethical concern with the making of imputations is the use of sexual stereotypes, which has been discussed in Canadian legal ethics literature. According to Professor Elaine Craig, defence counsel in sexual assault cases should not use arguments based on outdated social assumptions that have been “legally rejected as baseless and irrelevant”.33 For example, although the Canadian criminal code prohibits the admission of a complainant’s prior sexual history “for the purpose of inferring that prior sexual experience alone makes her more likely to have consented to the sex at issue in the allegation”, defence counsel in Canada have continued to rely on the legally rejected assumption.34 She suggested that “where a baseless social assumption has been categorically rejected either through legislative or jurisprudential reform”, the lawyer is “ethically obligated not to make arguments or pursue cross-examination that relies for its relevance or coherence on the rejected assumption”.35

Interestingly, an antiquated provision relating to an alleged victim’s credibility in rape cases was removed from the Evidence Act more than four years ago. Section 157(d) of the Evidence Act, which provided that the credit of the victim in a rape or attempted rape case may be impeached by showing that she is of generally immoral character, was repealed on 1 August 2012.36 At the Second Reading of the Evidence (Amendment) Bill on 14 February 2012, the Minister for Law noted that s 157(d) was “premised on antediluvian assumptions that a sexually active woman is less worthy of credit” and exposed sexual assault victims to “gratuitous, traumatising and insulting cross-examination”.37

In both Ong Jack Hong and Ng Jun Xian, the High Court rejected similar legally irrelevant stereotypes, namely, a victim who was sexually active cannot be traumatised by the rape and a victim who was allegedly of immoral character was partly responsible for the sexual assault. The fact that these imputations were made in submissions on sentence, and not in cross-examination, does not appear to be an ethically distinguishing feature, especially since the victim is usually not present in court to address such imputations.

IV. Time for Ethical Reform?

Based on the analysis in Part III, two reasons why ethical reform may be needed for the making of imputations against complainants of sexual offences are: (a) to make the existing ethical framework more coherent; and (b) to reduce the perpetuation of stereotypical imputations.

On the coherence of the ethical framework, proponents of the status quo may point to the robustness of the PCR 2015 which has adopted a principles-based approach.38 In this regard, in interpreting rules 12(4) and (5), defence counsel must not only take into account the general ethical principles articulated in rule 4, but also the two rule-specific principles set out in rule 12(1). These two principles require defence counsel to act “in a manner which is consistent with the administration of justice when dealing with any witness” and “exercise [his] own judgment both as to the substance and form of the questions put or statements made to a witness”. The same approach would also apply to the interpretation of rule 14(7).

Moreover, concerns regarding stereotypical imputations may be addressed by a number of ethical rules in the PCR 2015. For example, a legal practitioner must not mislead or attempt to mislead the Court (rule 9(2)(a)) or concoct any evidence or contrive any fact (rule 9(2)(g)). Also, a legal practitioner is prohibited from fabricating facts or evidence (rule 9(2)(b)) or advancing any submission which the practitioner knows or ought reasonably to know is contrary to the law (rule 9(2)(f)).

Notwithstanding the array of existing ethical constraints, there are three wider justifications why ethical reform is preferable.

Firstly, from a public policy perspective, Xu Jiadong observed that “the improper humiliation of victims of sexual offences during cross-examination could discourage future victims from coming forward”.39 Indeed, it must be a key objective of criminal proceedings that complainants of sexual offences are not subjected to unnecessary trauma, as otherwise the integrity of the proceedings would be undermined. If complainants are not assured that a fully coherent ethical framework exists to restrain defence counsel from, in Wellman’s words, throwing the dirt, it may lead to under-reporting of sexual offences.

Secondly, as observed above, the current ethical limits of making imputations are primarily defined by the limits prescribed in the Evidence Act pertaining to cross-examination. But such evidential limits do not consider the perspective of the complainant to whom the imputation is directed. In this regard, it is useful to refer to rule 21.8.2 of the Australian Solicitors’ Conduct Rules, which deals specifically with imputations made by defence counsel during cross-examination in sexual assault cases. This rule requires a solicitor to “take into account any particular vulnerability of the witness in the manner and tone of the questions that the solicitor asks” [emphasis added].40 Adopting the Australian rule may encourage defence counsel to become more attuned to the sensitivities of the complainant’s position (for instance, if the complainant is a minor), but it would require a paradigm shift to a slightly less adversarial mindset in criminal proceedings that is not fixated purely on the limits prescribed in the Evidence Act.

Finally, the existing ethical framework has not kept pace with changes in society regarding assumptions of the credit of complainants of sexual offences. Although s 157(d) of the Evidence Act was repealed in 2012, the underlying sexual stereotype which was rejected has not permeated into the ethical consciousness of the legal profession as rules 12(4), 12(5) and 14(7) of the PCR 2015 were left substantially unchanged from the previous ethical regime.41 At the very least, it may be helpful to insert a rule-specific principle in rule 12 of the PCR 2015 which reflects the following best practice guideline stipulated in the Code of Practice for the Conduct of Criminal Proceedings by the Prosecution and the Defence that was developed jointly by the Attorney-General’s Chambers and the Law Society of Singapore in 2013:

Prosecutors and Defence Counsel should in all cases:

… (b) conduct the examination of all witnesses fairly, objectively, and with due regard for the dignity and legitimate privacy of the witness, and without seeking to intimidate or humiliate the witness.42

V. Conclusion

Defending persons accused of sexual offences has been said to be “a personally taxing and frequently thankless” task, with lawyers “sometimes unfairly vilified for the legal services that they provide”.43 The purpose of this article is not to make that task harder for defence counsel, but to highlight why and how the PCR 2015 should be strengthened to give clearer guidance on the ethical limits of making imputations, which is in the interests of all stakeholders in the criminal justice system. This article takes the first step in encouraging conversations within and beyond the criminal Bar on this important area of lawyers’ ethics.

► Alvin Chen*

General Counsel, Legal and Compliance

RHTLaw Taylor Wessing LLP

E-mail: [email protected]

* The views expressed in this article are the personal views of the author and do not represent the views of RHTLaw Taylor Wessing LLP.

Notes

1 (United States of America: Grand Central Publishing, 1960), p 251.

2 Jeffrey Pinsler SC, Legal Profession (Professional Conduct) Rules 2015: A Commentary (Singapore: Academy Publishing, 2016), p 310.

3 [2016] SGMC 38.

4 Ibid, at [100], [101] and [103].

5 Ibid, at [104].

6 Ibid, at [106]–[107].

7 Ibid, at [111].

8 Ibid, at [98].

9 Ibid, at [110].

10 Francis L. Wellman, The Art of Cross-Examination (Fourth Edition, United States of America: Simon & Schuster, 1997).

11 Ibid, pp 202–03.

12 [2016] 5 SLR 166.

13 Ibid, at [23].

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 [2016] SGHC 286.

19 Ibid, at [40].

20 Ibid.

21 Ibid, at [41].

22 Ibid.

23 Ibid, at [42].

24 Ibid, at [43].

25 Ibid.

26 Davinder Singh SC, ‘Cross-Examination’ in Eleanor Wong et al (eds), Modern Advocacy: Perspectives from Singapore (Singapore: Academy Publishing, 2008), 103 at 124, para 07.096.

27 Ibid, at 126, para 07.100.

28 Supra (note 3), at [103].

29 Supra (note 26), at 126, para 07.101.

30 Supra (note 2), p 311, para 12.016.

31 Section 148(a).

32 Section 148(c).

33 Elaine Craig, “The Ethical Obligations of Defence Counsel in Sexual Assault Cases” (2014) 51(2) Osgoode Hall Law Journal 427 at 430.

34 Ibid, at 432, 438.

35 Ibid, at 462.

36 Evidence (Amendment) Act 2012 (Act 4 of 2012).

37 Parliamentary Debates Singapore, vol 88, at page 1128 (14 February 2012).

38 For a more detailed discussion of this approach, see Alvin Chen & Helena Whalen-Bridge, Understanding Lawyers’ Ethics in Singapore (Singapore: Lexis-Nexis, 2016), paras 1.21-1.25 and 1.43-1.45.

39 Supra (note 3), at [109].

40 Law Council of Australia, 24 August 2015 http://www.lawcouncil.asn.au/lawcouncil/images/Aus_Solicitors_Conduct_Rules.pdf.

41 See rules 60(h), 61(a) and 80 of the Legal Profession (Professional Conduct) Rules (Cap 161, R1, 2010 Rev Ed).

42 Paragraph 39(b).

43 Elaine Craig, “The Ethical Identity of Sexual Assault Lawyers” (2015-2016) 47 Ottawa Law Review 73 at 77.