Edge of Tomorrow: Singapore’s Debt-Restructuring Regime Revisedi

Singapore’s revisions to its insolvency and debt-restructuring regimes aims to challenge traditional jurisdictions such as the United States and England as a centre for international debt-restructuring. The revisions include the adoption of the UNCITRAL Model Law on Cross-Border Insolvency, embracing the principles of modified universalism.

Summary

1. The Companies (Amendment) Bill 20171 (the “Bill”) – passed into law on its second reading on 10 March 20172 – intends to introduce four sets of wide-ranging amendments3 to the Companies Act (Cap. 50) (the “Act”).4 One such set involves a significant overhaul of Singapore’s debt-restructuring and insolvency regime provisions. These changes have come into effect as of 23 May 2017.5 This article examines these changes to the status quo and what they mean for Singapore’s push to become an international centre for debt-restructuring.

2. The envisaged changes include:

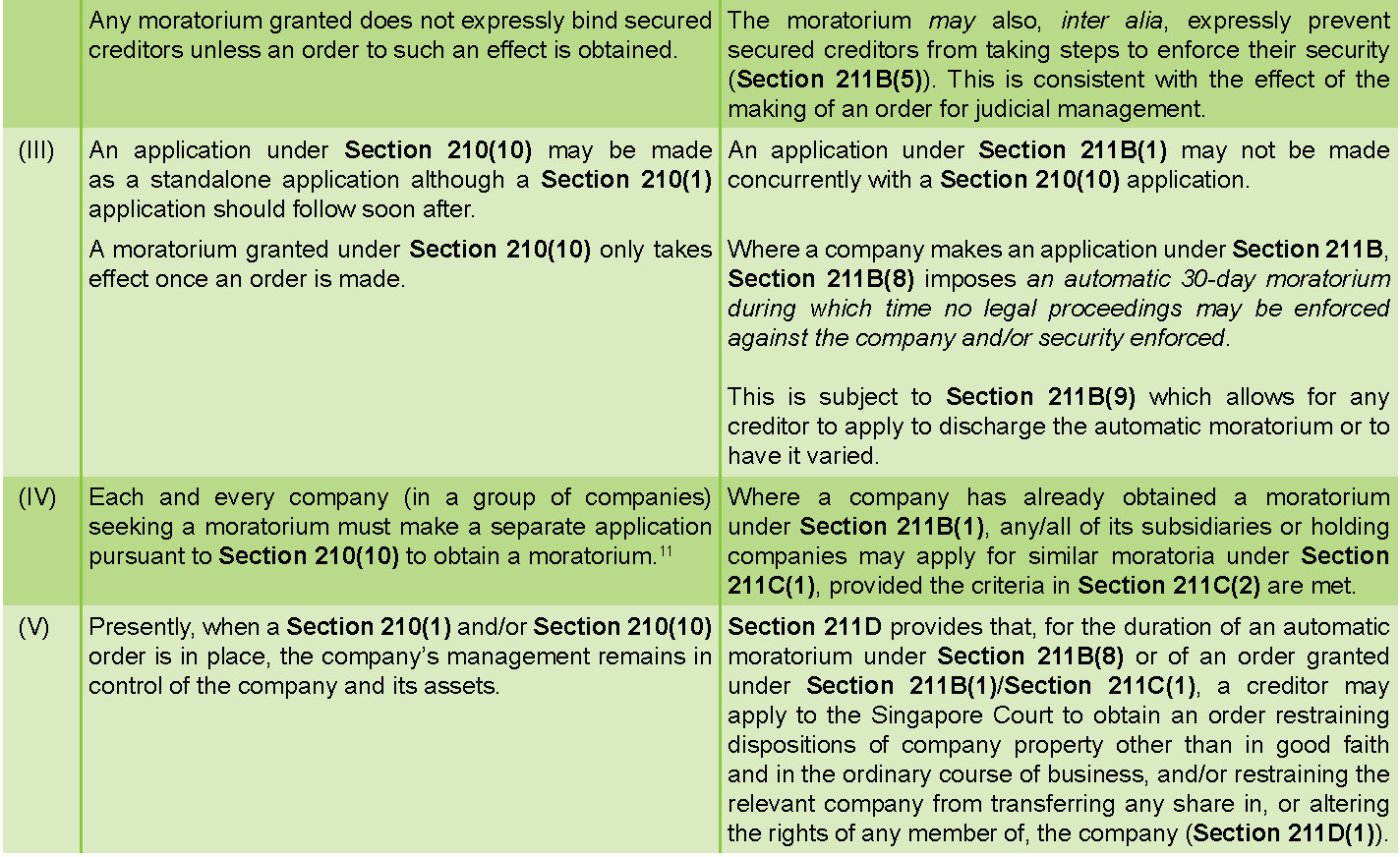

2.1 enhanced “cram-down” provisions which enable the Singapore Court to cram down a group of dissenting creditors in the context of voting to approve a scheme of arrangement (a “scheme”) in certain, limited circumstances;

2.2 enhanced, extra-territorial “moratorium” provisions in both judicial management and scheme applications, similar to those imposed in US-style “Chapter 11” proceedings;

2.3 the availability of the judicial management regime to foreign companies (provided they meet the criteria set out in the revised Section 351);

2.4 the abolishment of the ring-fencing rule in the winding up of foreign companies;6

2.5 the ability of the Singapore Court to order that any rescue financing provided in a restructuring (whether effected via a scheme or a judicial management) will have “super priority” status, discussed at paragraphs 9 and 10 below;

2.6 the availability of “pre-packaged” sales in schemes, discussed at paragraphs 14 and 15 below;

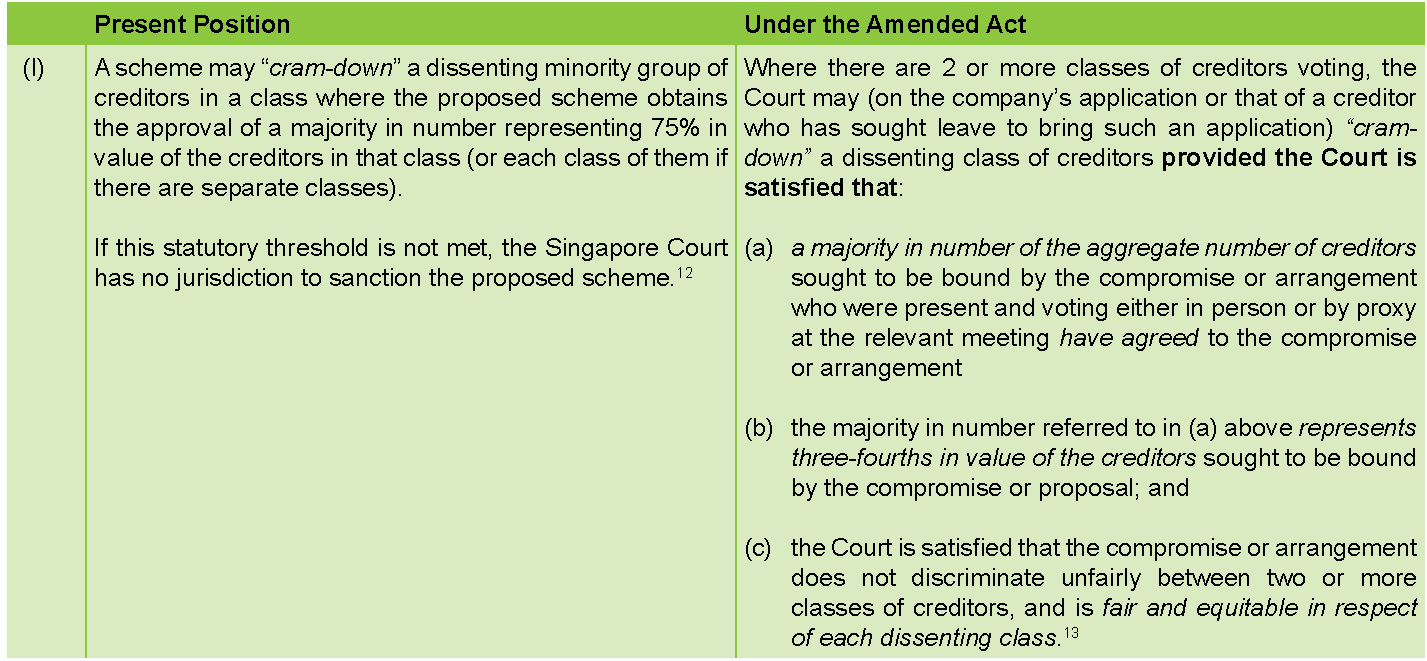

2.7 the enactment of the UNCITRAL Model Law on Cross Border Insolvency (the “Model Law”); and

2.8 the statutory codification of certain common law principles and concepts such as a company’s centre of main interests (“COMI”) in determining whether the Singapore Court ought to invoke its jurisdiction over a foreign company to make orders relating to judicial management or schemes.

3. The relevance of these changes cannot be overstated, particularly given the wall of maturing corporate debt that Singapore will have to contend with in the near future – S$38 billlion of local bonds are set to fall due from the time of writing through to 2020.7 Should any issuers default on repayment of these debts, these new provisions may be tested. This may indeed be a likely eventuality given the current complexion of the oil, gas and shipping landscapes, and the financial headwinds expected over the next few years.

Statutory Codification of “COMI” Principles

4. The COMI principles are relevant to the amendments to Section 351, which provide that a foreign company may only be wound up in the following circumstances:

Either

4.1 the foreign company is dissolved, has ceased to have a place of business in Singapore or has a place of business in Singapore only for the purpose of winding up its affairs or has ceased to carry on business in Singapore;

4.2 the foreign company is unable to pay its debts; or

4.3 the Singapore Court is of the opinion that it is just and equitable that the foreign company should be wound up;

And

4.4 the foreign company has a substantial connection with Singapore, for which determination the Singapore Court may take into account the presence of the following factors in respect of the foreign company:

(a) Singapore is the COMI of the foreign company;

(b) The foreign company is carrying on business in Singapore or has a place of business in Singapore;

(c) The foreign company is a foreign company that is registered under Division 2 of Part XI of the Act;

(d) The foreign company has substantial assets in Singapore;

(e) The foreign company has chosen Singapore law as the law governing a loan or other transaction or the law governing the resolution of disputes arising out of or in connection with a loan or other transaction; and/or

(f) The foreign company has submitted to the jurisdiction of the Singapore Court for the resolution of disputes relating to a loan or other transaction.

5. Consequently, if the foreign company is able to persuade the Court that it meets the requirements set out at paragraph 5 above, the Singapore Court may, in the exercise of its discretion,8 make orders relating to schemes and/or judicial management in respect of that foreign company.

6. Local companies, on the other hand, as creatures of the Act, will generally always be in a position to invoke the provisions of the Act.

Schemes of Arrangement (Sections 211A to 211I)

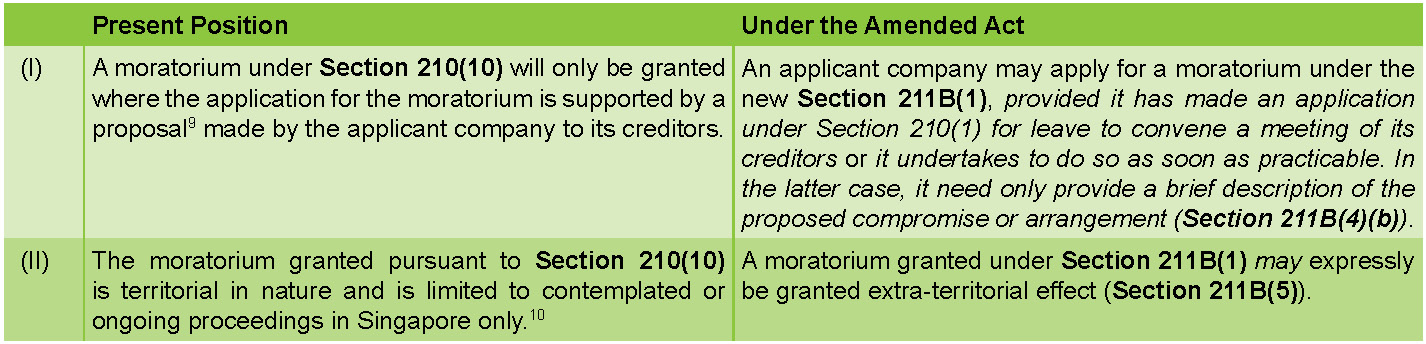

7. The four main changes to the scheme regime are:

7.1 the extension of the scope of the moratorium which the Singapore Court may order (which brings the moratorium in line with the automatic stay procedures applicable in judicial management, including a stay of realisation of security interests);

7.2 an automatic 30-day moratorium arising once an application for leave to convene a meeting of creditors is made (or is intended to be made);

7.3 the power of the Singapore Courts to cram-down a dissenting group of creditors in certain circumstances; and

7.4 new provisions relating to rescue-financing and the priority given to such individuals or institutions providing rescue finance.

Enhanced Moratorium Provisions

Enhanced “Cram-Down” Provisions

Rescue Financing

8. The introduction of “super priority” provisions for rescue financing is intended to incentivise and protect both existing and/or new investors seeking to inject fresh capital into the distressed company.

9. In general terms, where such an existing or new investor comes forward to inject fresh capital and/or relieve the company from its liabilities under a proposed scheme, the Singapore Court may order that the new investor enjoy “super priority” in respect of such funds injected or obligations incurred, and may do so by:

9.1 treating the debt as a cost or expense of winding up;

9.2 giving the debt priority over all other preferential debts;

9.3 securing the debt with a security interest over the company’s property, whether subject to an existing interest or not; or

9.4 where the property in question is already subject to a security interest, granting the rescue financier security that is subject to, equal or superior to an existing security interest.14

10. It can, therefore, be anticipated that the creation of the “super priority” status of rescue finance may open up new markets and/or business opportunities for banks, financial institutions, private equity and/or distressed debt funds to invest in economically sound, but financially strapped companies, safe in the knowledge that their rescue capital would be accorded priority.

Expedited Scheme Approval

11. The newly-introduced Section 211I grants the Court the power to sanction a proposed scheme without the applicant having to apply for leave to call for a meeting of creditors. Further, the Singapore Court may even sanction a proposed scheme without an actual meeting, provided that the Court is satisfied that, had a meeting been held, it would have obtained the relevant approval of the applicant’s creditors.

12. The burden of proof in invoking this provision is likely to be highly onerous. However, in appropriate cases (an obvious example being in situations where the supporting creditor or creditors, representing a majority in number, clearly have more than 75% in value support the scheme), this new provision is highly likely to result in significant savings of both time and costs.

13. Where the scheme in question concerns a sale of all or substantially all of the company’s assets, and qualifies for the expedited scheme approval procedure, this will essentially facilitate the “pre-pack” sale of the scheme company’s assets to a previously identified buyer.

14. This arrangement is common in England, where “pre-pack” sales often occur in administration, the English equivalent of Singapore’s judicial management regime. If successful, an expedited scheme could save significant costs and time, and possibly result in greater preservation of value of the relevant assets.

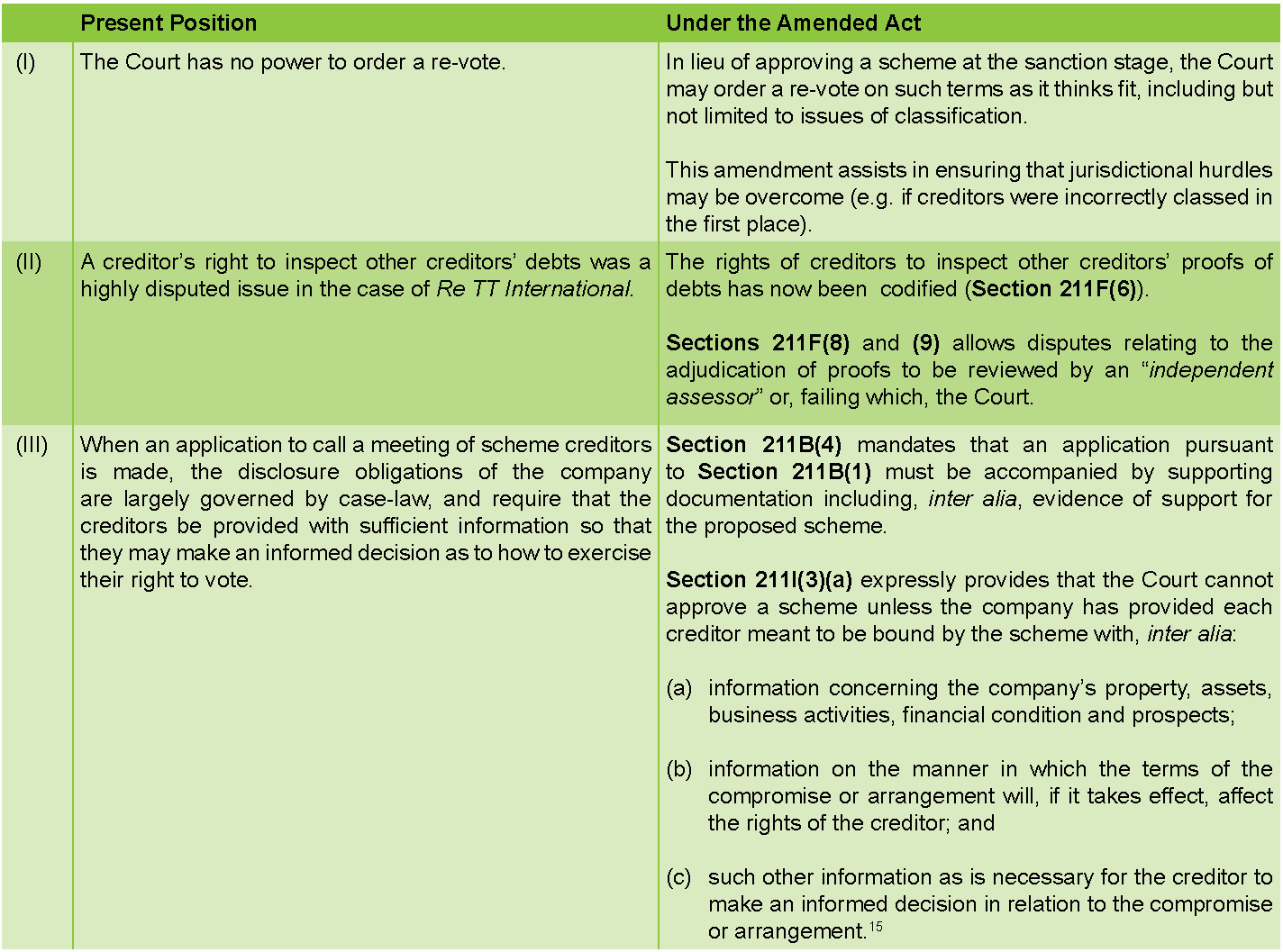

Enhanced Creditor Protection and Flexibility

Various principles enshrined in the common law have now been codified in the revised Act. Further amendments and changes have also been introduced to deal with difficulties which previously arose in scheme applications.

Revisions to the Judicial Management Regime

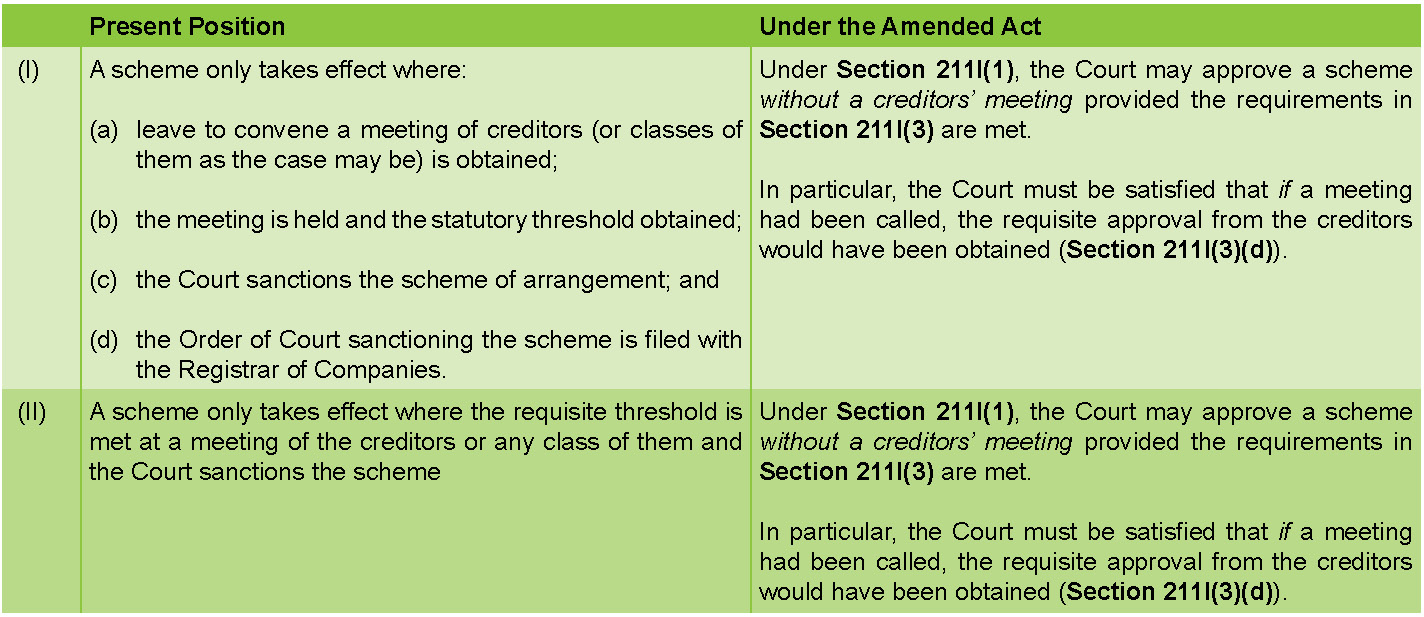

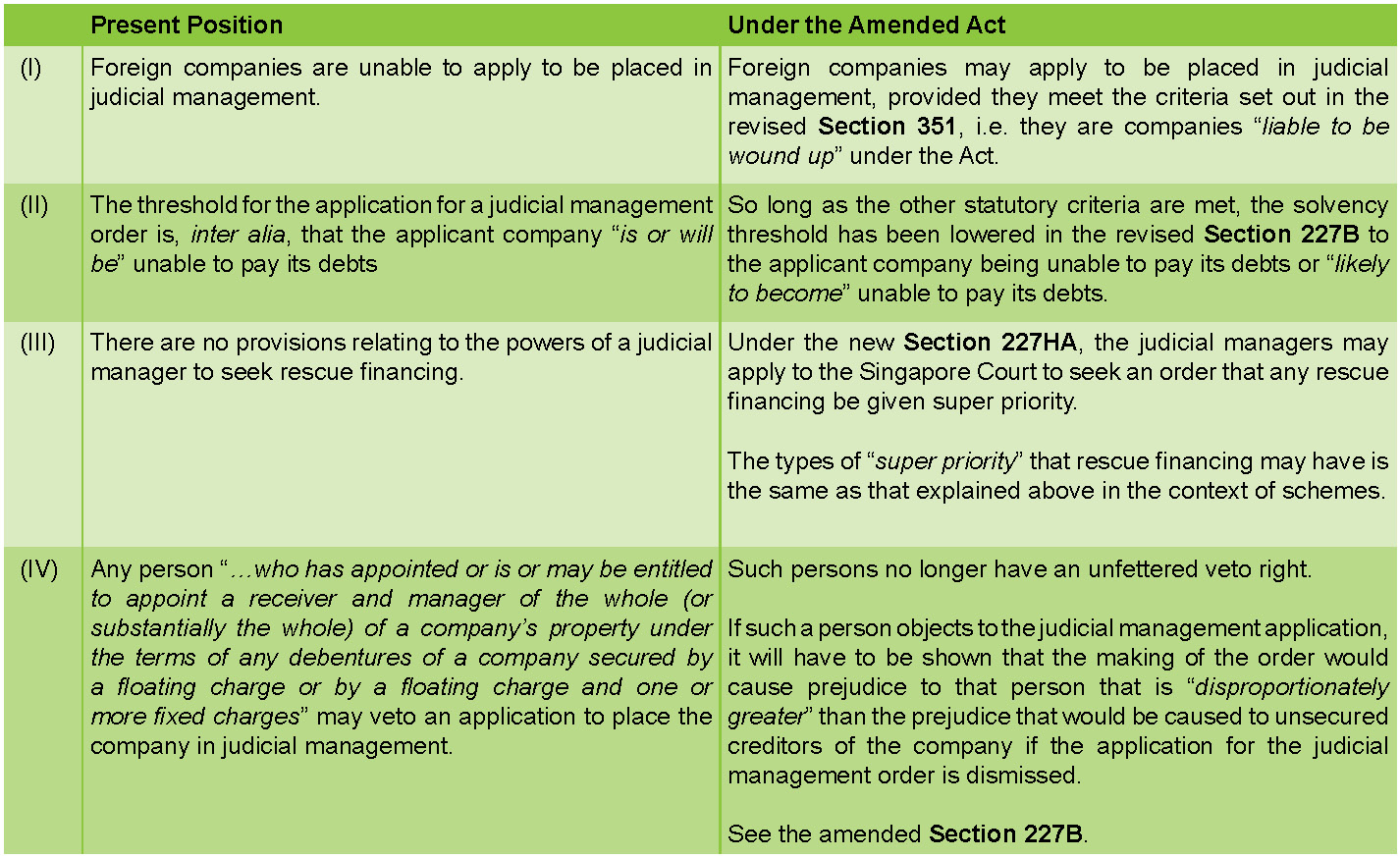

16. The changes to Singapore’s judicial management regime chiefly relate to:

16.1 the availability of judicial management to foreign companies;

16.2 the solvency threshold for the revised judicial management regime to apply;

16.3 the availability of “super priority” for rescue financing; and

16.4 the right of a creditor having fixed and floating security over all (or substantially all) the company’s assets to object to a company being placed under judicial management.

The status quo will be altered as follows:

18. These key changes are likely to result in:

18.1 foreign companies opting to undergo judicial management here instead of pursuing parallel proceedings in their home country. This would likely be appropriate where such companies have significant assets and/or interests in Singapore, whether directly or otherwise.

18.2 more rescue financing arrangements being entered into, given the greater incentive for interested parties to put judicial managers in funds where “super priority” is available. This would, in turn, result in more robust efforts to rescue companies and/or enforce their legal rights.

18.3 greater protection of the interests of the company’s general body of unsecured creditors, with the ability of particular secured creditors to veto a judicial management application curtailed.

The Model Law

19. Finally, Singapore has adopted the Model Law via the introduction of Section 354B, and abolished the oft-criticised ring-fencing provision in respect of the liquidation of foreign companies under Part XI of the Act.

20. The formal adoption of the Model Law will have the effect of codifying international cooperation with other member states in parallel insolvency proceedings. For example, the Model Law provides the basis for:

20.1 the recognition of the ongoing insolvency process in one jurisdiction as being a foreign main (or non-main) proceeding as the case may be, with other jurisdictions either facilitating or taking the lead of the insolvency process;

20.2 a step towards “globalising” the compulsory, collective process to maximise value in cross-border insolvency scenarios, with the appropriate liquidator / administrator / representative taking charge of the insolvency process and getting in the insolvent company’s assets from and enforcing its rights in ancillary jurisdictions;

20.3 a statutory basis to repatriate locally-based assets to the principal place of liquidation (the jurisdiction of the main proceeding), subject to the protection of certain statutory rights accruing to the creditors of the jurisdiction from which the assets are repatriated; and

20.4 the necessary infrastructure for communication between the respective courts and/or insolvency professionals engaged in the various jurisdictions involved in the cross-border insolvency, to ensure a smooth and orderly realisation of assets on a regional, international or global scale.

21. Such cooperation will be facilitated by provisions such as the newly-introduced Section 354B(2), which specifically provides that, in interpreting the Model Law, the following documents are relevant:16

(a) Documents relating to the Model Law, issued or prepared by the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law and its working group; and

(b) The Guide to Enactment of the UNCITRAL Model Law on Cross-Border Insolvency (UN document 15 A/CN.9/442).17

22. Taken together with the abolishment of the ring-fencing provision, the long-awaited18 introduction of the Model Law marks a departure from Singapore’s traditional territorial approach to cross-border insolvency proceedings, and a shift towards modified universalism. The Honourable Judicial Commissioner Aedit Abdullah observed:19

In cross-border insolvency, there has been a general movement away from the traditional, territorial focus on the interests of the local creditors, towards recognition that universal cooperation between jurisdictions is a necessary part of the contemporary world. Under a Universalist approach, one court takes the lead while other courts assist in administering the liquidation. This is the most conductive to the orderly conduct of business and resolution of business failures across jurisdictions. The tone of the approach in Beluga and the telegraphed adoption of the UNCITRAL Model Law on Cross-Border Insolvency (30 May 1997) (the “Model Law”) in Singapore are indicators that Singapore is warming to Universalist notions in its insolvency regime.

[emphasis added]

23. This emerging approach to cross-border insolvency is demonstrated in recent Singapore High Court decisions20 embracing such principles.

24. Given this general trend, it is likely that this approach will be embraced by the Singapore Courts even for cross-border insolvency issues involving jurisdictions which have not adopted the Model Law.

25. Such an approach would be consistent with that at common law, as set out by Lord Hoffmann in Re HIH Casualty and General Insurance Ltd [2008] 1 WLR 852 (“Re HIH”)21, and endorsed by the Singapore High Court in Re Opti-Medix:

… The primary rule of private international law which seems to me applicable to this case is the principle of (modified) universalism, which has been the golden thread running through English cross-border insolvency law since the eighteenth century. That principle requires that English courts should, so far as is consistent with justice and UK public policy, co-operate with the courts in the country of the principal liquidation to ensure that all the company’s assets are distributed to its creditors under a single system of distribution ...

Concluding Remarks

26. Given the scale of the amendments, this commentary is by no means an exhaustive guide to the changes and amendments to Singapore’s debt-restructuring and insolvency regimes. Instead, it seeks to identify and explain the key changes to the extent possible at this preliminary stage. Indeed, only time will tell how the Singapore Court will interpret these new amendments.

27. Distressed companies within the region (or with interests in the region) may now look to Singapore as a debt-restructuring hub with the relevant infrastructure in place to secure a successful debt-restructuring. It is also envisaged that it will be easier for debtor companies (whether foreign or local) to seek interim protection from the Singapore Courts in respect of prospective or ongoing claims against them, whether in Singapore or elsewhere.

28. It is hoped that the Singapore Courts will remain vigilant, however, against the potential abuse of the amended provisions by wrongdoers seeking to remain in situ to, for example, hide their wrongdoings or asset-strip the company, despite inevitable insolvency – a matter which the Courts must be alive to

29. Further, and as mentioned above, the introduction of the “super priority” provisions in respect of rescue financing may have the effect of being a “market maker” insofar as it may open up new markets and opportunities for the financially-savvy investor who is willing to fund a turnaround.

30. Finally, what is evidently clear is that, by the amendments into law, Singapore has backed up its express aspirations to be a debt-restructuring destination, and positioning itself to challenge the United States (where restructuring is far more expensive) and England (which does not have moratorium proceedings as part of its scheme provisions) as the destination of first choice for restructuring.

31. Singapore’s track record in establishing itself as a “go to” jurisdiction in the fields of international arbitration, banking and financial services bodes well for its bold move to develop itself as an international debt-restructuring hub. Though only time will tell how successful this particular endeavour will be, we believe that Singapore will rise to the occasion.

► Thio Shen Yi, SC

Joint Managing Partner

TSMP Law Corporation

Notes

i The contents of this update are owned by TSMP Law Corporation and subject to copyright protection under the laws of the Republic of Singapore (as may from time to time be amended). No part of this update may be reproduced, licensed, sold, published, transmitted, modified, adapted, publicly displayed, broadcast (including storage in any medium by electronic means whether or not transiently for any purpose save as permitted herein) without the prior written permission of TSMP Law Corporation. Please note that whilst the information in this Update is correct to the best of our knowledge and belief at the time of writing, it is only intended to prove a general guide to the subject matter and should not be treated as a substitute for specific professional advice for any particular course of action as such information may not suit your specific business, operational and/or commercial requirements. You are therefore urged to seek legal advice for your specific situation.

1 Last accessed on June 15, 2017.

2 Last accessed on June 15, 2017.

3 Last accessed on June 15, 2017.

4 References to “Sections” shall refer to Sections in the Act, as amended in or introduced by the Bill.

5 See the Government E-Gazette notification dated 22 May 2017 available online at http://www.egazette.com.sg/pdf.aspx?ct=sls&yr=2017&filename=17sls244.pdf .

6 c.f. Legislative ring-fencing will remain in effect in the case of specific classes of financial institutions (specified by MAS), such as banks and insurance companies.

7 See “Singapore’s looming debt wall fuels concern after Ezra stumbles” (The Business Times, 20 March 2017) (last accessed on June 15, 2017).

8 See Re Pacific Andes Resources Development Ltd and other matters [2016] SGHC 210 (“Re PARD”) at [33], per the Honourable Judicial Commissioner Kannan Ramesh (as his Honour then was).

9 In Re Conchubar Aromatics Ltd [2015] SGHC 322 (“Re Conchubar”) at [12], the Honourable Judicial Commissioner Aedit Abdullah held that the proposal had to be sufficiently particularized such that the Court could consider whether “…on the face of the proposal the Court could conclude that there was a reasonable prospect of the scheme working and being acceptable to the general run of creditors.”

10 See Re PARD at [16] to [17].

11 See Re PARD at [10].

12 See The Royal Bank of Scotland NV (formerly known as ABN Amro Bank NV) and others v TT International Ltd and another appeal [2012] 2 SLR 213 (“Re TT International”) at [178].

13 In determining what is fair and equitable, the Singapore Court must be satisfied, inter alia, that no creditor in the dissenting class receives under the terms of the scheme an amount that is lower than what he is estimated to receive in the event that the company is wound up (Section 211H(4)(a)). Other requirements are imposed by Section 211H(4)(b) as may be applicable.

14 The Court will only order the creation of a security interest equal or superior to an existing security interest over property where there is “adequate protection” provided for the existing security holder (Section 211E(1)(d)(ii)). The meaning of “adequate protection” is explicated in Section 211E(6)(a) to (c).

15 A statutory codification of, amongst other things, the principles enunciated in the Court of Appeal decision in Wah Yuen Electrical Engineering Pte Ltd v Singapore Cables Manufacturers Pte Ltd [2003] 3 SLR(R) 629 at [24].

16 Note that nothing in Section 354B(2) affects the Court’s power to adopt a purposive interpretation of any written law in accordance with Section 9A of the Interpretation Act (Cap. 1).

17 Last accessed on June 15, 2017.

18 See the Summary of the Recommendations by the Insolvency Law Reform Committee, 2013 at [26] (last accessed on June 15, 2017).

19 See Re Opti-Medix Ltd (in liquidation) and anor matter [2016] SGHC 108 (“Re Opti-Medix”) at [17].

20 See Re Taisoo Suk (as foreign representative of Hanjin Shipping Co Ltd) [2016] SGHC 195; and Re Gulf Pacific Shipping Ltd (in creditors’ voluntary liquidation) and others [2016] SGHC 287.

21 Re HIH at [30].