|

Inside the Bar |

Reports in Custody and Access

Disputes — When, Why and

What Are

They?

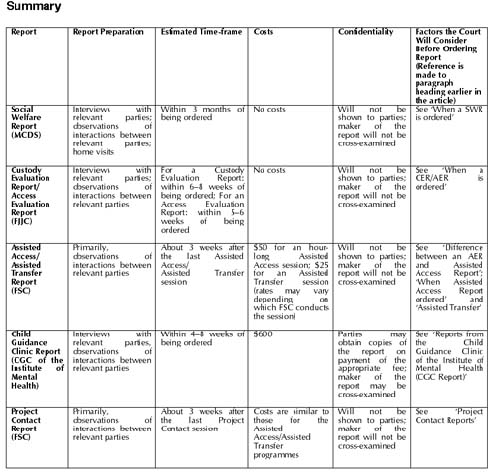

The guidelines set out are not intended to be exhaustive. There may be some overlap in the different categories of reports, in that different types of reports may be equally suitable for the same situation. Which type of report is appropriate and which type of report is ordered is entirely a matter for the court’s discretion and will depend on the circumstances of the individual case. In order to assist the court’s decision, in this regard, lawyers should be familiar with the facts of their case, so that they may advise the court on the same. Such facts would include (but are not limited to): the age of the child in question, his relationships with each of his parents, his siblings and any significant third parties, his academic performance and behaviour in school, his living and sleeping arrangements and his mental and physical health.

The following reports in relation to custody and access disputes may be ordered:

(a) the Social Welfare Report — by the Ministry of Community Development and Sports (‘MCDS’);

(b) the Custody Evaluation Report or Access Evaluation Report — by the Family and Juvenile Justice Centre (‘FJJC’);

(c) the Assisted Access Report or the Assisted Transfer Report — by a Family Service Centre (‘FSC’) participating in the Assisted Access/Assisted Transfer programme;

(d) the Child Guidance Clinic Report — by the Child Guidance Clinic (‘CGC’) of the Institute of Mental Health; and

(e) the Project Contact Report — by an FSC participating in the Project Contact programme.

The court will order one of the reports set out in the previous paragraph if it is of the view that the input of someone trained and experienced in child welfare would be useful in coming to a decision on what orders to make in relation to the custody and/or access dispute between parties.2 Reports may be ordered by the deputy registrar at the ancillary pre-trial conference, the court mediator or the judge hearing the ancillary matters.3

A SWR is prepared by an MCDS officer, who is trained in child welfare issues and custody dispute investigation.

When the court orders a SWR, it will also make certain standard orders. A copy of these standard orders will be handed to the parties. These are orders to ensure that parties co-operate with MCDS in the investigation process for the SWR. An example of one such order is that the parties are to attend all appointments made with the MCDS officer punctually. The court will also hand each of the parties a form entitled ‘Annex A’, which the parties will have to fill in and send to the court within two working days. The information required in Annex A includes the contact numbers and addresses of each party and the child/children, as well as the birth certificate or NRIC numbers of the child/children. Upon receipt of the relevant Annex A forms from the parties, the Family Registry will then transmit the order for the SWR to MCDS, for their further action. MCDS will then contact the parties and commence their investigations.

The MCDS officer will interview both parents, as well as any significant third parties in order to prepare the SWR. The officer will also speak to the child (if he or she is old enough to converse with the officer) and observe the child’s interactions with the respective parties. Home visits will be made by the MCDS officer to the child’s home and/or the homes of other relatives, such as the grandparents, if necessary.4

The SWR will usually be furnished to the court within three months of the making of the SWR order. The SWR will be sent directly to the court.

Generally, SWRs are ordered for disputes over care and control, as opposed to disputes over access. However, a SWR may be ordered in respect of a dispute over whether or not the non-custodial parent should be granted overnight access (since that involves spending time in a particular place, which may make a home visit necessary). Where there is no dispute over care and control, but only a dispute over sole or joint custody, a SWR is unlikely to be ordered, as this is more of a legal issue and submissions and affidavits by the parties themselves should suffice.

Appropriate circumstances in which to order a SWR would include those situations where:

(a) the child is not really able to express himself verbally (usually if he is under 10-years-old); and/or

(b) the custody/access dispute is a serious one — usually a situation where both parties have indicated consistently during the ancillary pre-trial conferences conducted since the granting of the decree nisi that they will be contesting the issue; and/or

(c) there are allegations about the place the child would be spending a significant amount of time (either because of access or because he would be cared for in that place) which would make home visits useful. For example, if there are allegations that the home environment is noisy and messy, MCDS can examine the child’s sleeping and studying arrangements there; and/or

(d) there are specific allegations such as physical or sexual abuse, alcoholism or drug use.

Parties do not have to pay for a SWR to be prepared.

The SWR is a confidential report, for the use of the judge hearing the custody and access issues. As a general rule, it will not be shown to parties and the maker of the report will not be cross-examined.

FJJC furnishes two types of reports. One type is the Custody Evaluation Report (‘CER’), which is to assist the court in resolving custody disputes, the other type is the Access Evaluation Report (‘AER’), to assist the court in resolving access disputes (ie whether access should take place, for how long, whether it should be supervised or not, whether there should be overnight access, whether the parent should be able to bring the child overseas for a holiday, etc).

FJJC reports are prepared by the FJJC counsellors, all of whom have a background either in social work, counselling or psychology and who have been trained in the preparation of custody and access evaluation reports.

After the court has ordered a CER/AER, the Family Court Registry will contact the parties to attend at the Family Court for interviews.

A CER requires about 40 hours to prepare, which involves interviews with the parents, the child and any significant third parties, as well as time for writing the report. The interviews take place over a six to eight week period, at the end of which the CER will be written. An AER would take a slightly shorter time (about five to six weeks) to prepare.

The difference between a SWR and a CER/AER is that during the preparation of the latter, FJJC counsellors will not do home visits. Their reports are prepared based on interviews and observations of interactions which take place in the Family Court.

Appropriate circumstances in which to order a CER/AER would include those situations where:

(a) the child is able to express himself well verbally (usually if he is over 10-years-old); and/or

(b) there are allegations that the child is alienated from one parent and of the brain-washing of the child by one parent; and/or

(c) very acrimonious custody and access disputes; and/or

(d) where home visits may not be necessary, because there are no allegations of the home environment being unsuitable, the key issues being the nature of the relationships between each of the parties.

Parties do not have to pay for a CER/AER to be prepared.

Like the SWR, the FJJC report is confidential, for the use of the judge hearing the custody and access issues. As a general rule, it will not be shown to parties and the maker of the report will not be cross-examined.

In the Assisted Access programme, the non-custodial parent has access to the child at a participating FSC (for example, Tanjong Pagar FSC, Serangoon Moral FSC and Loving Heart FSC), under the supervision of a counsellor. In the Assisted Transfer programme, the child is handed over for access and/or returned after access at a participating FSC, under the supervision of a counsellor.

If an order for Assisted Access/Assisted Transfer is made, the court will usually order the same to continue for a period of six to eight weeks, or even longer. At the end of this period, a report will be written by the FSC which has conducted the Assisted Access/Assisted Transfer sessions. This report will be sent directly to the court. Which of the participating FSCs is chosen to conduct the Assisted Access/Assisted Transfer programme for a particular case will depend on the geographical location of the FSC in relation to each party’s home and the availability of suitable time-slots for the Assisted Access/Assisted Transfer sessions at the FSC.

AERs are written based on several interview sessions which the FJJC counselor conducts with the parties. In an Assisted Access case, the FSC counsellor will play a less interactive role, focusing more on observing the dynamics between the parties and the children.

To allow for such in-depth (and relatively non-interactive) observation of the parties and the children by the FSC counsellor, the number of Assisted Access sessions that must take place before an Assisted Access report can be written will usually be greater than the number of interview sessions conducted for the purpose of writing the AER. Thus, it would take about three to four weeks longer for the Assisted Access report to be written than the AER. The Assisted Access sessions would also be fixed at a set time and for a set time period on a weekly basis, whereas the timing and duration of the counselling sessions for the purpose of writing the AER would be more flexible.

Due to the shorter time-frame, and more flexible timing for the sessions, the court would usually order an AER rather than an Assisted Access Report, in relation to an access dispute. This is unless it is of the view that the in-depth observation which the Assisted Access programme would provide is necessary to investigate issues of the child’s safety and relationship with the non-custodial parent. Appropriate situations for ordering an Assisted Access Report would include those where:

(a) the child is not really able to express himself verbally (usually if he is under 10-years-old); and/or

(b) there are very serious allegations of alcohol abuse, child abuse, family violence, etc against the non-custodial parent, but there is some evidence that the relationship between the non-custodial parent and the child is actually quite sound; and/or

(c) there seems to be little or no bonding between the non-custodial parent and the child; and/or

(d) where home visits may not be necessary, because there are no allegations of the home environment being unsuitable, the key issue being the nature of the relationship between the non-custodial parent and the child.

It should be noted that the Assisted Access sessions are not primarily intended for the non-custodial parent to enjoy more access time with the child, but for the counsellor to observe the non-custodial parent and child together and to assess the nature of the relationship between them and also to assess its future progress.

Long term supervised access sessions to enable the non-custodial parent and child to bond may be made by the court under the Project Contact programme (see below).

Assisted Transfer is suitable in cases where the relationship between the mother and the father is very acrimonious, but the relationship between each of the parents and the child seems to be relatively sound. If the non-custodial parent is granted more than two hours’ interim access time by the court and is allowed to bring the child out, for example, to go to a shopping centre, or to his own home and so on, then an Assisted Transfer order would be appropriate, not an Assisted Access order.

The Assisted Transfer will reduce the opportunity for the parents to quarrel when the child is handed over, thus reducing trauma for the child. The Assisted Transfer Report will enable the court to ascertain the causes of the conflicts that seem to arise and the trauma that the child seems to experience, whenever the child is handed over for or returned from, access. It will also enable the court to assess what are the best arrangements to make for the smooth and harmonious handover of the child in future.

It will take about three weeks from the last Assisted Access/Assisted Transfer session for the Assisted Access/Assisted Transfer Report to be furnished to the court. Parties must pay the fees for the Assisted Access/Assisted Transfer Programme. Thus, when ordering the parties to attend the Assisted Access/Assisted Transfer Programme, the court will also make an order as to which party should bear the costs of the report or that the costs should be split equally (but the court will then specify who is to make payment first). The amount of fees payable to the relevant FSC will vary, depending on which FSC conducts the Assisted Access/Transfer programme. But, on average, it costs $50 for an hour-long Assisted Access session and $25 for an Assisted Transfer session.

Like the SWR and the CER/AER, the Assisted Access/Assisted Transfer Report is confidential, for the use of the judge hearing the custody and access issues. As a general rule, it will not be shown to parties and the maker of the report will not be cross-examined.

A CGC Report is prepared by the Child Guidance Clinic of the Institute of Mental Health. When the court orders a CGC Report, the Family Registry will write to the CGC to inform it of the order which has been made. The CGC will contact the parties thereafter to arrange for them to attend at the CGC for interviews.

The CGC Report is sent directly to the court, about four to eight weeks after it is ordered. Parties can obtain copies of the CGC Report from CGC, if they wish and upon payment of the appropriate fee.

A CGC Report would only be ordered in relation to a custody and/or access dispute, in the most exceptional of cases, where the court is of the view that the input of a psychiatrist is required. Appropriate circumstances would include those situations where:

(a) A party is alleged to have exhibited behaviour consistent with a mental disorder (for example, paranoia, seeing evil spirits, extreme confusion); and/or

(b) A party is suspected of having a medical condition (eg alcoholism, mild mental retardation) that may diminish his capacity to fulfil his parenting duties; and/or

(c) There are allegations that the child’s mental health is being seriously affected or would be seriously affected by the child’s interaction (or lack thereof) with his parents — and that the child may suffer a mental problem as a result; and/or

(d) There are serious allegations of child sexual or physical abuse.

Like Assisted Access/Transfer Reports, CGC reports must be paid for by the parties. Thus, when ordering a CGC report, the court will also make an order as to which party should bear the costs of the report or that the costs are to be split equally between them (but the court will then specify who is to make payment first). The average cost of a CGC report is about $600.5

Under the Project Contact programme, supervised access between the non-custodial parent and the child will be ordered to take place at a participating FSC for a certain time period, usually a period of more than eight weeks. A supervised transfer order may also be made under the Project Contact programme. Which of the participating FSCs is chosen to conduct the Project Contact programme for a particular case will depend on the geographical location of the FSC in relation to each party’s home and the availability of suitable time-slots for the Project Contact sessions at the FSC.

The Project Contact order will usually be made at the same time that final orders on the custody and access issues are made.

The court may or may not order the FSC to furnish a report on the Project Contact sessions at the end of the supervised access period. If a Project Contact Report is ordered, the court will usually review the case after the Project Contact Report is furnished. The time-frame for obtaining the Project Contact Report, the costs of taking part in the Project Contact programme and the confidentiality of the Project Contact Report would be the same as for the Assisted Access/Assisted Transfer programmes.

Deputy Registrar Lim Hui Min

Family Court

|

Endnotes 1 This article does not deal with reports from private psychiatrists, which may be obtained by the parties of their own volition, or ordered by the court, either of its own motion or upon the application of one or both of the parties to the custody and/or access dispute. 2 See s 130 (court to have regard to advice of welfare officers, etc) of the Women’s Charter (Cap 353): When considering any question relating to the custody of any child, the court shall, whenever it is practicable, take the advice of some person, whether or not a public officer, who is trained or experienced in child welfare but shall not be bound to follow such advice. 3 It should be noted that when parties are ordered to attend counselling at FJJC, an FJJC report will not be furnished, unless the court makes a specific order for such a report to be furnished. For example, at the ancillary pre-trial conference, if parties inform the deputy registrar that there is a serious custody and/or access dispute between the parties, the deputy registrar may order parties to attend counselling, to see if parties can come to an amicable agreement amongst themselves with the help of a counsellor, without ordering FJJC to furnish a report in respect of such counselling sessions. If the parties attend a mediation session to discuss, inter alia, the custody and access issues before they have attended a counselling session at FJJC, and the court mediator is of the view that a counsellor’s input would be useful in assisting him to mediate the matter, he may adjourn the mediation session and order the parties to attend counselling at FJJC. The court mediator will also not order a report to be furnished by FJJC in respect of such counselling sessions, if he is of the view that the confidential notes from the FJJC counsellor conducting the said sessions will suffice. 4 For more information on the custody dispute investigation process, please see the article by MCDS in the July 2003 issue of The Singapore Law Gazette entitled ‘Custody Dispute: Social Investigation’. 5 This figure is subject to change by the CGC. |