|

FEATURE |

Recent Changes to the Trustees Act and

Civil Law Act

This article takes a brief look at some of the more important amendments made by

the Trustees (Amendment) Act 2000 to the Trustees Act and the Civil Law Act and

how they may affect trust companies, professional trustees and also solicitors

in their day-to-day practice.

Introduction

The Trustees (Amendment) Act 2004 came into force on 15 December 2004 with important amendments to the Trustees Act and the Civil Law Act, in particular relating to trusts, settlements and other dispositions. The net result of the amendments is a welcome and long overdue modernisation of the law. This article takes a brief look at some of the more important amendments and how they may affect trust companies, professional trustees and also solicitors in their day-to-day practice. References to the Act are references to the Trustees Act (Cap 337) as amended by the Trustees (Amendment) Act 2004.

The purpose of the amendments is to facilitate and promote wealth management in Singapore through the use of trusts and trustee services. This is part of the Government’s broader aim to enhance Singapore’s position as a leading financial and wealth management centre. The intention is to attract more foreign banking business and private investment to Singapore, in particular the wealth of sophisticated high net worth individuals.

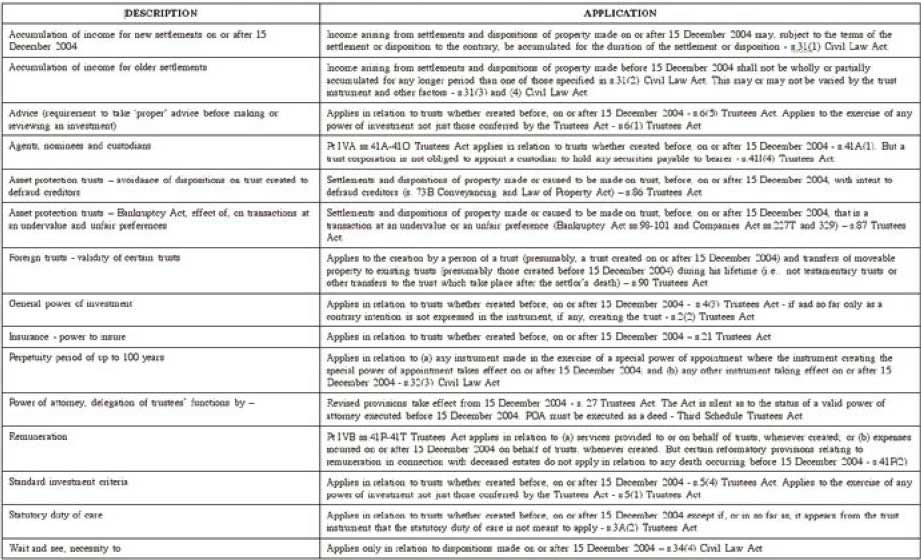

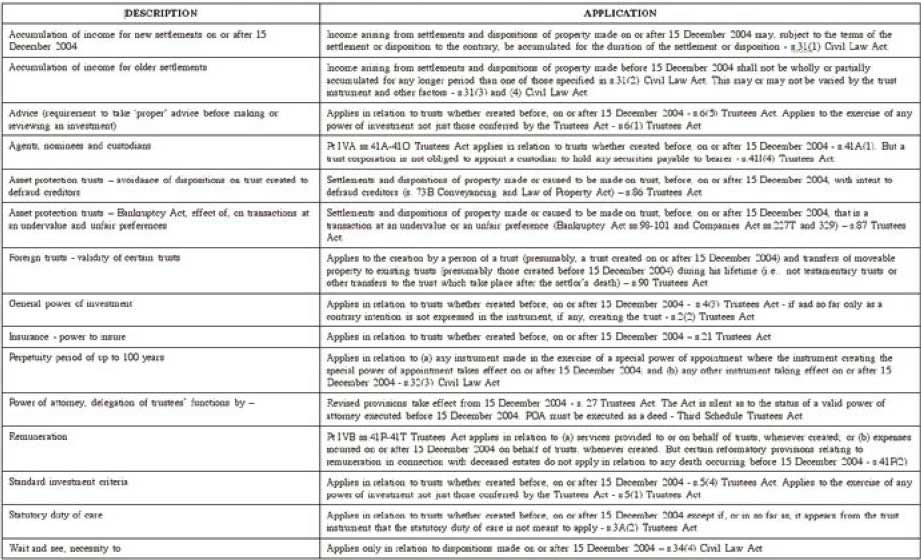

But what about the changes as they affect practitioners and trustees? Is there anything that a solicitor needs to change in his day-to-day practice in Singapore? How much of a difference does it make to the business of day-to-day private trusts management and administration? The answer to all these questions, in that purely technical context, can only be: ‘probably, not very much’. But there are some changes of importance in daily practice. First, the changes to the Civil Law Act which introduce a fixed perpetuity period and also the concept of ‘wait and see’ to replace the perplexing common law rules. Second, an important clarification of the law relating to wills and estates which should enable an officer of a trust company, a solicitor or other professional person appointed as executor to witness a client’s will without losing the benefit of the charging clause. Third, certain changes to the Trustees Act and to the Civil Law Act apply to trusts created or dispositions made before the amendments came into effect1 and some do not. Similarly, there are some provisions, relating to wills, which may not apply in cases where the testator died before 15 December 2004. Given the nature of wills, trusts and property law generally, it may be appropriate even decades from now to determine a matter by reference to this important date. The table may serve as a useful ready reference.

Main Amendments

A new general power of investment coupled with a statutory standard of care

Gone is the old very restrictive authorised investments regime previously applicable to trustees who lacked broader investment powers. Subject to any contrary provision in the trust instrument,2 s 4 of the Act provides that a trustee may make any kind of investment as if absolutely entitled to the assets of the trust. The safeguards are: (a) a statutory duty of care requiring the trustee to exercise such skill and care as is reasonable in the circumstances including his own actual, professed or deemed special skill or knowledge;3 (b) regard to specified ‘standard investment criteria’ including ‘the suitability to the trust of investments of the same kind as any particular investment proposed to be made or retained and of that particular investment as an investment of that kind’ and ‘the need for diversification of investments of the trust, in so far as is appropriate to the circumstances of the trust’;4 and (c) a requirement that the trustee obtain and consider proper advice before exercising powers of investment.5

The statutory standard of care expected of a trustee who has not ‘contracted out’ is very clearly related to the trustee’s position in terms of expertise or professed expertise and professionalism. Thus, a trustee who is a solicitor, accountant, stock broker or trust company, for example, would be expected to demonstrate a very high standard of care. Whereas a lower standard of care may be expected of a trustee who is a lay person — one who lacks any special knowledge, experience or expertise. Many executors and administrators of deceased estates may fall into the latter category, the appointment being often nothing more than a family matter. But one may wonder whether such lay trustees, often taking office by default, might in fact have to demonstrate a higher standard of care than a professional trustee who has the benefit of an appropriate exclusion clause in the trust instrument. Much would depend on the extent to which professional trustees choose to exclude the statutory standard of care at the risk of prejudice to their own credibility.

The requirement under s 6 of the Act to obtain and consider proper advice means advice from ‘a person who is reasonably believed by the trustee to be qualified to give such advice by his ability in and practical experience of financial and other matters relating to the proposed investment’. But curiously, in sub-s 6(3) it is provided that a trustee ‘need not obtain the advice required ... if he reasonably concludes that in all the circumstances it is unnecessary or inappropriate to do so’. A sort of voluntary directive, then; but one which a trustee might not want to treat with flippancy.

So has anything really changed in s 3A to 6 of the Act? Well, ‘Yes and No’ might be a reasonably accurate answer. This is because the previous ‘authorised investment’ provisions which have been repealed were in practice always excluded by professional trustees and trust companies and largely ignored by lay trustees. Professional trustees and trust companies would usually be expected to demonstrate a high level of skill and care, for their reputation depends upon it. And no doubt they have always taken proper advice on investments or proposed investments when appropriate and will continue to so do. The introduction of these provisions and the repeal of the old list of authorised investments does mean that unit trust schemes no longer need to be authorised by the Act. So, the old provisions in Part VII of the Trustees Act have been deleted.

Settlor’s powers

For many years it has been the practice for settlors to reserve to themselves certain powers in relation to asset management and investment decisions despite the danger that the purpose of the trust may be eroded if the extent of the settlor’s involvement might cast into doubt the validity of the trust. But the desire of settlors to be actively involved in investment decisions is a natural consequence of private investors becoming more knowledgeable and sophisticated. To facilitate this, sub-s 90(5) of the Act provides that no trust or settlement of property on trust shall be invalid by reason only that the settlor reserves such powers to himself. However, trustees who agree to subordinate their powers in this way should take care to exclude the statutory duty of care in s 3A. But the trustee might be wary of excluding such duty in all cases in standard documentation lest the settlor who does not want to reserve investment powers to himself be discouraged from employing that trustee’s services.

New provisions on powers of attorney and delegation by trustees

Previously, a trustee could delegate his functions by power of attorney only as long as the trustee remained outside Singapore for a period exceeding 14 days. Section 27 of the Act reforms the rules with regard to power of attorney granted by a trustee. There is now no requirement that the trustee be outside Singapore and there is a new prescribed form of power of attorney6 which did not previously exist. Additionally, Part IVA of the Act7 is a new set of provisions to clarify the law relating to agents, nominees and custodians. In the employment of agents, there are detailed provisions as to what functions may be delegated by the trustees of private trusts and charitable trusts respectively. It deals with important matters such as the standard of care expected of persons to whom the trustee has delegated his powers and functions.

A detailed recital of all the new provisions of Part IVA is outside the scope of this brief article. But clearly the ability of trustees, particularly trust companies, to appoint attorneys-in-fact, agents, nominees and custodians and a detailed set of rules governing such appointments is a necessary part of modern banking and trusts administration. It is also a necessary extension of the general powers of investment introduced by s 4 of the Act (and/or contained in the trust instrument) and the standards of care and attention to the details of investments pertaining to that.

On the technical side, practitioners should take note of the prescribed form of power of attorney in the Third Schedule of the Act which must be executed as a deed. Or a form of power of attorney to like effect which is expressed to be made under s 27(5) of the Act may be used. The validity of a power of attorney should be limited to 18 months or less and notice should be given within seven days to all other trustees and persons with a power to appoint new trustees.8 Though somewhat technical requirements, these are provisions which might have unfortunate consequences if they are overlooked.

Introduction of a 100-year perpetuity period

As a matter of public policy, non-charitable trusts have always been subject to a common law requirement that they be limited in duration to a life or lives in being plus 21 years, during which time the trust property must vest in the beneficiaries. This is the perpetuity period arising from the so-called ‘modern’ rule against perpetuities — a bit of common law already several centuries old. The common law rules were difficult to understand and apply with the result that some trusts were actually void in law, no doubt with unintended consequences. Now, there is a clear fixed period of 100 years9 which will be the maximum perpetuity period for any private trust established on or after 15 December 2004.

There is no longer any need in private trust deeds and wills to make perplexing references to King George of England and his many descendants, nor try to explain the purpose of this to an equally perplexed settlor or will maker. Practitioners and trustees should review their standard documentation to bring their perpetuity clauses into line with the new s 32 of the Civil Law Act. But there may be no damage done if they omit to do this. Parliament has clearly anticipated a degree of deleteriousness by providing in sub-s 32(2) that if the instrument refers to lives in being or to any perpetuity period exceeding 100 years, the perpetuity period shall be deemed to be a period of 100 years. This could also serve as an automatic fix for any trust being migrated to Singapore and which includes a contrary perpetuity clause.

Necessity to wait and see

In the past, some trusts, perhaps unfairly, have failed because of uncertainty as to whether the trust property would or would not vest in the beneficiary within the perpetuity period. Now, all such trusts will be treated as being valid until it is certain that the trust property will not vest in the beneficiary at all or would vest only after the end of the perpetuity period.10 This provision will save some new trusts and dispositions made on or after 15 December 2004 which might otherwise have failed.

To permit accumulation of income for the full duration of the settlement

The previous provisions giving power to trustees of maintenance, advancement or protection trusts to accumulate income during the minority or earlier marriage of a beneficiary continue to apply to settlements and dispositions of property made before 15 December 2004. But new provisions will allow accumulations for up to the whole of the life of the disposition or settlement if it was made on or after 15 December 2004, subject to contrary provisions in the relevant instrument.11 There are also new provisions to rationalise the rules relating to the shorter accumulation periods for trusts created before that date.12

To encourage foreigners to use Singapore trusts

Very much in line with the aim to promote Singapore as a leading centre of wealth management and encourage foreign private investment, is s 90 of the Act. Those who are not Singapore citizens or domiciles are excluded under certain circumstances specified in s 90 of the Act from forced inheritance and succession rules, thereby allaying fears about the enforceability of such trusts in Singapore. But there are some conditions attached. The person creating the trust or transferring movable property to the trust must have capacity to do so under either Singapore law, or the law of his domicile or nationality, or the proper law of the transfer. Furthermore, the trust must be expressed to be governed by Singapore law and the trustees must be resident in Singapore.

Furthermore, in ss 86 and 87 of the Act, the draftsman has thoughtfully drawn attention to provisions in the property and bankruptcy legislation dealing with settlements and dispositions which attempt to outwit creditors. For the avoidance of doubt, sub-s 86 of the Act points to sub-s 73B of the Conveyancing and Law of Property Act and provides that settlements and dispositions made on trust with intent to defraud creditors are voidable in accordance with that section. And sub-s 87 of the Act calls up ss 98 to 101 of the Bankruptcy Act and ss 227T and 329 of the Companies Act in relation to transactions at an undervalue and unfair preference. This is another example of ‘nothing much has changed’. But it looks good to an outsider who is not familiar with Singapore law and who may be reading only the Trustees Act 2004 when considering where to plant his trust. The ‘for avoidance of doubt’ clauses do two things, really. First, they indicate to the casual window shopper that Singapore is not a place to come and hide your ill-gotten gains, for that is not tolerated. Second, this little bit of candour helps to give additional integrity to the modernisation of the Trustees Act as a whole.

Wills and charging clauses

It has often been said that a solicitor who is appointed executor cannot witness the will. And neither can any of his partners, and preferably none of his staff. This is because, as executor, the solicitor would want to charge for his services and, therefore, would require a charging clause in the will. But if he or his partners or his staff witness the will, there is a danger that (because of s 10 of the Wills Act) the firm will lose the benefit of the charging clause if the charging clause may be construed as a gift. This, in turn, could require the unhappy solicitor to apply to court in case of doubt for a remuneration order to replace the benefit of the lost clause. Now, under sub-s 41Q of the Act, if the executor acts in a professional capacity or is a trust company, the charging clause will be considered for what it is — that is remuneration and not a gift.

Conclusion

Do the changes to our Trustees Act and Civil Law Act measure up to the promise of helping to enhance Singapore as a leading wealth management centre? They probably do for the time being. Though, no doubt, there will be further reviews of trusts law from time to time. Perhaps, for example, in the context of single purpose trusts, non-charitable purpose trusts and development in the areas of protector’s powers and duties and settlor’s reserved powers. The latter may be of particular importance to investors who have difficulty embracing the concept of parting with ownership, where necessary, as part of an efficient and attractive trust scheme. Only time will tell as to the efficacy of the present amendments and, in the context of that, the necessity for further legislative changes.

Hopefully, the objective of modernising the relevant laws has been well met by these amendments. And hopefully also the broader objective to enhance Singapore’s standing as a wealth management centre will be well met. Finally, it is hoped that the modernisation of the law will make things a little easier for the profession and for trust companies and will encourage more young lawyers and other professionals to step into the increasingly sophisticated area of estate planning, private investment and wealth management practice. No doubt they will be very much needed as the ships come in.

Simon D Trevethick

Colin Ng & Partners

E-mail: [email protected]

Endnotes:

1 15 December 2004 — Trustees (Amendment) Act (Commencement) Notification 2004 No S 702.

2 Sub-s 2(2) of the Act.

3 Ibid, s 3A.

4 Ibid, sub-s 5(3).

5 Ibid, s 6.

6 Ibid, sub-s 27(5) and Third Schedule.

7 Ibid, ss 41A to 41O).

8 Ibid, sub-ss 27(2)(b) and (4).

9 Ibid, s 89; and s 32 of the Civil Law Act (as amended by the Trustees (Amendment) Act 2004).

10 Ibid, s 34.

11 Ibid, s 31(1).

12 Ibid, s 31(2) which clarifies the law relating to accumulation of income.

Table to Show Applicability of Certain Changes Brought About by the Trustees (Amendment) Act 2004