|

FEATURE |

Sukuk are the Hollywood stars of Islamic finance. The article will describe the most salient features of the Sukuk financial papers. It is not an indepth analysis of legal and / or Shariah controversies and, therefore, details and nuances might be put aside in return for simplicity and accessibility to the conventional reader. The article aims to give a first glimpse into a realm that probably is unknown to the reader: the Kingdom of Sukuk.1

Sukuk ! Sukuk ! My Kingdom for a Sukuk ! –

A Brief Introduction in Sukuk Concepts

Introduction

Most of present day Sukuk are primarily aimed towards the conventional (fixed income) bond markets, that differ from the equity markets.2 They have developed to:

1. Steady and fixed income generation : pre-agreed interest rates – not dependent on any real underlying profit or loss;

2. Personal liabilities and claims on the borrower (independent of the success of the project);

3. Lower risk profile than outright equity investment (mostly ranking preferential to capital contributions and often secured); and

4. Usually mid-term maturity.

“Fixed income Sukuk” would probably strive to fit the following description:3

1. Stabilised, but not guaranteed income : based on underlying assets that tend to generate stable revenue streams;

2. No personal liability on the borrower and fully dependent on the success of the project / asset;

3. Lower risk profile because of specific choice asset / project and structuring;

4. Ranking pari passu amongst each other; and

5. Usually mid-term maturity.

The global bond markets are substantially larger than the equity markets4 and are sustained by the large institutional investors (pension funds, insurance companies etc). Not having access to that investor profile would be a serious constraint on the development of the Islamic financial markets.

But Riba (in conventional finance simplified to interest) prohibits the lending of money against interests and also impairs the trading of financial debt except at face value, so it appeared initially as if that enormous financial market might stay excluded to Islamic finance.

However, focusing on the two major attributes (risk management and fixed income), the Sukuk appeared to find its place.

The fixed income-like structure is attained by investing in and / or trading in underlying assets that generate a stable income or indirectly through partnership structures that typically (but not always) tend to transact in such stable income generating assets.

But stable income is not necessarily fixed income. Therefore, often smoothening of the revenue streams may be reached by:5

1. Building reserve funds (temporarily absorbing surplus and equalising later shortfalls);

2. Intermediate sale of assets to generate cash flow in order to timely service the projected profit stream; or even

3. Interest free advances given by the Manager that may be recuperated from later profits.

Owners’ risk is often reduced by taking up Takaful (Islamic acceptable insurance).

Furthermore, since the structures are built upon the value and the revenue streams of the underlying assets, risk management has given rise to:

1. Promises to buy the asset at maturity or default of the Sukuk (either at market value or historical value – for the capital amount and / or the expected revenues); and

2. Outright (mostly third party) guarantees.

Later on in this article, we will only touch upon some of the controversial issues; overall, we will limit ourselves to a short, introductory description of the general modus operandi of the Sukuk.

We will explain here, how, the introduction of the so-called asset backed Sukuk could play a pivotal role in further market developments.

Definition

AAOIFI :

“Investment Sukuk are certificates of equal value representing undivided shares in ownership of tangible assets, usufructs and services (in the ownership of) the assets of particular projects or special investment activity…”6

IFSB :

“Sukuk (plural of sakk), frequently referred to as ‘Islamic bonds’, are certificates with each sakk representing a proportional undivided ownership right in tangible assets, or a pool of predominantly tangible assets, or a business venture. These assets may be in a specific project or investment activity in accordance with Shariah rules and principles.”7

Securities Commission Malaysia :

“… any securities issued pursuant to any Shariah principles and concepts approved by the Shariah Advisory Council (“SAC”) of the SC as set out in Appendix 1 … (and subsequently) Appendix 1 (B) : A document or certificate which represents the value of an asset”8

The definition of the Bahraini-based AAIOIFI gives a clear, limitative list (tangible assets, usufructs, services, assets of particular projects, assets of special investment activity), whereas the Malaysia-based IFSB gives a broader definition (tangible assets, pool of predominantly tangible assets or business venture) whilst the Malaysia-based Securities Commission has a more vague definition (securities issued pursuant to any Shariah principles).

We will see here9 that the Malaysian definitions leave room for the introduction of financial assets such as receivables and debts in the pool of assets that form the Sukuk. The GC-based definition does not seem to allow this. Allowing or prohibiting the trading of Islamic debt is one of the big differentiators in Shariah interpretation between the GCC and Malaysia.

Sukuk = Islamic bond ?

A bond is generally perceived to be a debt instrument – much like an IOU – issued by the borrower to the lender(s), in a “cash now” transaction balanced with a “cash back later” with a profit (interest) for the lender(s) – simply put: a loan against interest.10

“Loans of money against interests being excluded, it would, however, be conceivable for an Islamic lender to try to issue such a financial instrument by incorporation of an Islamic debt into a debt instrument.11

Where for instance Malaysia has accepted the creation and tradability of such notes and bonds, this is at this time not the case in most other jurisdictions, just as in the GCC”.

As is already clear from the definition above, where the conventional bond holder has a financial claim on the borrower for payment of capital / interests, the Sukuk holds an equity claim upon an asset or business venture and / or the resulting revenue stream / profit (or loss) thereof.

Therefore, instead of a debt instrument, the Sukuk is said to be a quasi equity based financial instrument. Hence, translating Sukuk to “Islamic bond”12 might lead to unnecessary confusion. It would be better to name it an “Islamic investment certificate” etc.

Types of Sukuk

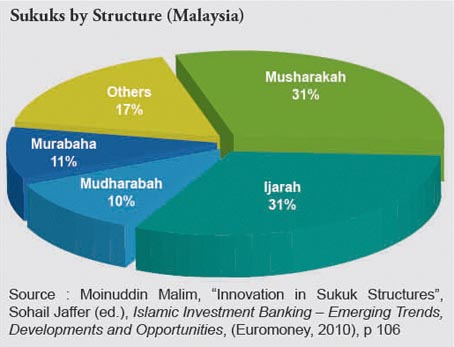

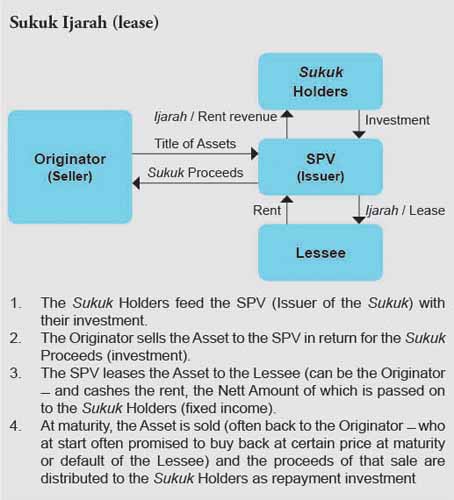

Whilst the AAOIFI Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (Bahrain) has recognised 14 different Sukuk structures, for now, compiled data for Malaysia show that the Ijarah (leasing), Musharakah (partnership), Mudarabah (partnership) and Murabaha (mark up sale) are by far the most common.

The reason is that it has so far appeared to be much easier to park stable income generating assets with lower risk profile in these structures (thus mimicking the behaviour of conventional bonds as close as possible). For instance: a commercial real estate could be inserted in a Sukuk Ijarah, Sukuk Musharakah or Sukuk Mudarabah. Mixed structures (co-mingling of Ijarah and Murabaha and so forth) are also spotted in the market.

Debt and money cannot be traded at a discount or profit according to Islamic law. A Sukuk whose assets are too liquid (more than 50 per cent cash), therefore, cannot be traded for more or less than face value at the stock exchange as if it were a regular bond. Sukuk Murabaha, therefore, will not be tradeable.14

Mostly, the Sukuk is issued through an SPV. Trust, fund and company structures have been used in various jurisdictions and in compliance with the different Mazhabs (Islamic schools of thought), next to the “authentic” Islamic partnerships (Musharakah15 and Mudarabah16).

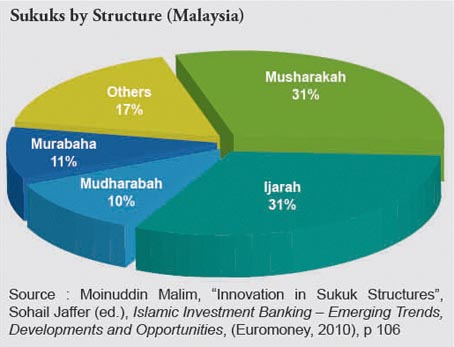

In general, the following classification can be made:

1. Sukuk based on sale (Murabaha, Salam, Istisna’ and Bai’Bithaman Ajil (“BBA”);17

2. Sukuk based on lease contracts (Ijarah and variations);

3. Sukuk based on partnership contracts (Musharakah and Mudarabah); and

4. Sukuk based on Agency (Wakalah bi Istithmar).18

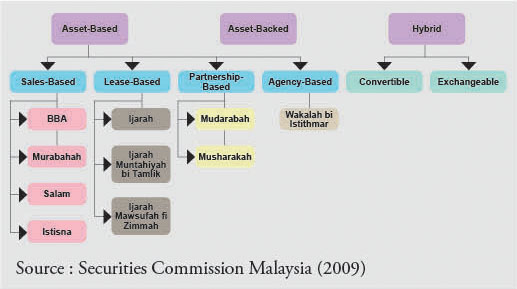

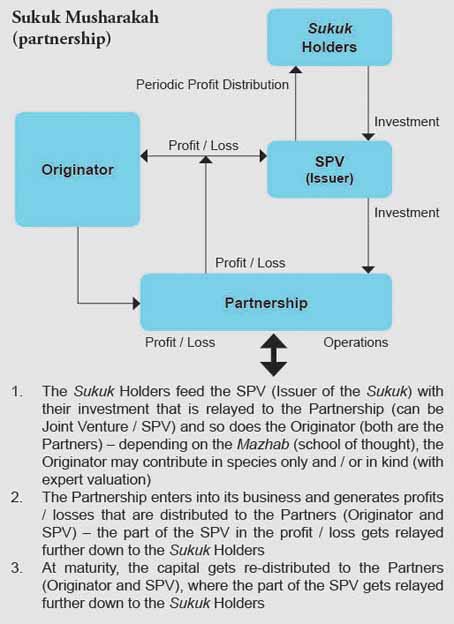

Below is a rough, schematic flow chart of the Sukuk Ijarah (lease) and a Sukuk Musharakah (partnership).

Every Sukuk Ijarah is not equal and can probably best be deducted by deduced some salient features of some “groundbreaking” issuances.19

In the 2004 Tabreed Financing Corporation Sukuk (US$100 million), the National Central Cooling Company (Originator) transferred full title of real estate assets to an SPV in return for the Sukuk Proceeds in a cash consideration. The assets then were leased back to the Originator in return for periodic lease rentals. The Originator promised to buy back said assets at maturity of the Sukuk at payment of the pre-agreed exercise price.20

In the 2002 Malaysian Global Sovereign Sukuk (US$600 million), the Malaysian Government (Originator) only transferred the beneficial titles (retaining the actual legal titles because of legal constraints) of designated real estate in return for the Sukuk Proceeds in a cash consideration. The real estate was than leased back to the Originator, who had promised to buy the assets back at the maturity of the Sukuk against payment of a pre-agreed exercise price. 21

The 2002 MUIS Musharakah Sukuk (Sin$35 million) is a transparent use of the Musharakah Sukuk. The MUIS Majelis Igama Islam Singapura (“MUIS”) (on behalf of its Waqf) entered into a Musharakah project with the Investors. Both parties tabled capital contributions (the Investors received their Sukuk as proof thereof) for the acquisition of some prime property in Singapore that subsequently was leased out.

The lease rentals were to be shared between the Musharakah partners (MUIS and the Sukuk Holders) and the MUIS gradually bought the Sukuk Holders out by redeeming the outstanding Sukuk certificates. The MUIS used its part of the lease rental and other sources. At the end of the Sukuk tenure, the Waqf owned all of the real estate. Here the Sukuk Holders had direct ownership rights in the real estate held by the Musharakah.22

Asset Backed and Asset Based / Pay-Through and Pass-Through

In order to have a good understanding of the difference between asset based and asset backed, we will turn to the distinction as described by the IFSB Islamic Financial Services Board (Malaysia):23

(a) An asset backed Sukuk structure … would leave the holders of Sukuk to bear any losses in case of the impairment of the assets. The applicable risks are those of the underlying assets ...

(b) An asset based Sukuk structure with a repurchase undertaking (binding promise) by the originator: the issuer purchases the assets, leases them on behalf of the investors and issues the Sukuk. Normally, the assets are leased back to the originator in a sale-and leaseback type of transaction. The applicable credit risk is that of the originator, subject to any Shari`ah-compliant credit enhancement by the issuer ...

Such structures are sometimes referred to as “pay-through” structures, since the income from the assets is paid to the investors through the issuer.

(c) A so-called “pass-through” asset based Sukuk structure: a separate issuing entity purchases the underlying assets from the originator, packages them into a pool and acts as the issuer of the Sukuk. This issuing entity requires the originator to give the holders recourse, but provides Shari`ah-compliant credit enhancement by guaranteeing repayment in case of default by the originator.

The asset backed Sukuk leads to a full transfer of legal ownership of the underlying asset (asset is lost = all is lost) while asset based Sukuk involve recourse to the Originator or the Issuer (but not to the asset). True sale, non-recourse and adequate bankruptcy remoteness are the keywords to distinguish asset backed Sukuk from asset based Sukuk.

In the asset based Sukuk, the Common Law “trust” mostly was used as the core element of the transaction, whereby the legal title of the ownership of the assets stayed at the Trustee and only the beneficial ownership shifted through the Sukuk towards the Sukuk holders. Because of the specific structuring,24 in case of bankruptcy proceedings, the Sukuk holders often stayed behind with a non-preferential claim, ranking equal with other creditors.

The wide spread use of trusts in asset based structuring had some advantages:

1. Whilst the Sukuk holders got paid by the revenue streams of the specific assets, the Sukuk could benefit from the credit rating of the originator of the Sukuk (just as a regular bond could do); and

2. Some uncertainties in bankruptcy regulations and the “true sale” concept in GCC jurisdictions could be by-passed, next to the fact that some Issuers25 had regulatory constraints in alienating assets to (foreign) entities and persons.

It might be expected that the use of asset backed Sukuk will expand, because it is perceived to be more real equity based (true sale and recourse to the asset only). It will be obvious that such might influence the pricing of the security and probably also the composition of its investor base. On the other hand, it would enhance positioning of the product – maybe even create a new asset class – and innovation. The challenges and opportunities have been recognised by not only the market players, but also by industry bodies such as the IIFM International Islamic Finance Market (Bahrain) that already plans a documentation standardisation preparing for a “Master Agreement”.26

Hybrids – Convertible and Exchangeable Sukuk

Both convertible and exchangeable Sukuk have been accepted. A convertible Sukuk will give the holder the right (but not the obligation) to exchange his paper into a pre-determined number of equity in the issuer at a pre-determined price. An exchangeable Sukuk will give the holder the right to do so in a third party company.

Some Shariah Issues: Profit Sharing – Promises to Buy and Guarantees

Profit and Loss Sharing

As a general rule of thumb, in a partnership, loss is borne by the capital contributors pro rata their share whilst profits may get shared according to agreement.

Subordination constructions in the form of tranching (some tranches of the Sukuk absorb losses before the other tranches) have, however, surfaced, but they remain debatable at first sight and further developments have to be awaited.

Secondly, it can be observed that preferential profit sharing in classical thinking usually was discussed in favor of a partner contributing labour and not so much as a differentiator between capital contribution partners,27 but also different forms of waterfalls (certain tranches of the Sukuk have first / unequal right to profit sharing) have emerged.

These constructions are spotted more in the IABS (asset backed) than in the asset based structures and such by tying the rights of the different tranches to different asset of the pool.28 Both issues require further study from a Shariah point of view.

Guarantee

A third party capital guarantee is more or less generally accepted because those guarantees are deemed to be benevolent / free of charge in Islamic law. Since it makes little business sense to engage in a guarantee, it, therefore, is difficult to find guarantors. Bear in mind that the existence of the guarantee should be independent from the main contract itself.29

More complicated would be a capital guarantee issued by the Wakil / Musharik or Mudharib30 in the partnerships.31 In the Sukuk Mudarabah, for instance, the Mudarib is the manager / trustee and he / she cannot be held responsible for any losses except those due to negligence, mismanagement and dishonesty. To allow extension of that principle would cut both ways: it grows the responsibility of the Mudarib and excludes the capital risk for the Rabb al-Mal / Sukuk holder. This is not allowed. Also in the Sukuk Musharakah the rule goes that all losses must be borne by the Investors proportionate to their investments and guarantee clauses undermining this principle32 are not allowed.

Promise to Buy

At Sukuk maturity there are usually residual assets. That can be the real estate that was the object of the Sukuk Ijarah etc. A Promise to Buy (that consequently gets realised) aims to sell the remaining assets down according to contract agreement in order to make the SPV liquid again and distribute the money back to the Investors / Sukuk holders.

Often, the market value of such assets is difficult (if not impossible) to determine and then pre-agreed sums or formula are integrated in the “Promises”. These usually then tend to boil down to a repayment of the initial investment (sometimes outstanding profit shares included). Sometimes, regulatory constraints make the assets flow back to the (sovereign) issuers and / or do not allow assets to be sold to foreigners and there is no other option than to have the assets go back to the original owner.

Again, third party Promises to Buy have been more or less widely accepted.

As faras the Sukuk Ijarah (based on lease) is concerned, there appears to be agreements to allow such promises, certainly when at market value. But for the partnership Sukuk (Mudarabah – Musharalah), the situation is more complex. Any such Promise to Buy in any case may not result in a perceived or real guarantee for capital and / or profit (not acceptable). The debate still continues.

These aspects constitute an area of the Sukuk structuring that still is in motion and future developments will lead the way.

Singapore

Singapore has publicly reiterated its aim to become a hub for Islamic finance in Asia. The vast financial resources that are available in the local banking market – significantly oriented towards fixed income financing – are an open invitation and responsibility by the nation to that end.

A first milestone was reached in 2009 when the Monetary Authority of Singapore (“MAS”) established its S$200 million Sukuk Al-Ijarah Trust Certificate Issuance Program.

The most remarkable year has been 2010, being the first SG$ denominated Khazanah Sukuk Wakala for S$1.5 billion (RM3.6 billion). That year saw the year of the largest Sukuk issuance in Singapore, the largest SGD issuance by a foreign issuer in Singapore, the first SGD Sukuk issuance out of MIFC initiative and the longest-tenured SGD Sukuk.

On the regulatory front, the MAS has introduced changes to the regulations to enable the application of Islamic finance (both Sukuk issuances as regular financing techniques) in Singapore by – amongst others – allowing Singapore-based banks to offer Ijarah-based financing33 and to enter into so called diminishing Musharaka financing and spot Murabaha transactions34 etc. Further, the tax treatment of certain Shariah-compliant financing instruments was harmonised with that of conventional products. Since April 2010, banks in Singapore have been allowed to enter into Istisnah or project finance transactions.35

This type of finance will in the future not only be restricted to the GCC or in jurisdictions that hold important Muslim populations. Instead, Korea, Japan, Hong Kong, Luxembourg etc are conventional jurisdictions where non-Muslim entrepreneurs aspire to realise projects that are oriented towards real economy or that want to attract the attention of affluent Muslim investors.

The Singapore Government and the MAS have timously set the pace to catch up with market developments, building on the well developed financial sector within its borders.

Conclusion

Some of the Sukuk has been conceived in such ways as to appeal to the conventional fixed income investor and, therefore, the pricing is balanced against the pricing on the bond markets. Trading also takes place on the bond markets. It is, however, not a pure debt instrument.

Whilst the similarity had been beneficial so far for the Sukuk market, on a downturn, Sukuk holders claimed36 to have been confused and had “bond expectations” 37 (performance based upon solvency of the Originator (or even the underlying “sovereign” reference shareholder therein) and not on the performance of the asset / business venture.

Some of that suggested confusion could have been due to suggested behaviour by the Issuers themselves, but also due to the willingness of the rating agencies to streamline the Sukuk ratings on the conventional ratings and to treat the Sukuk as if they were debt instruments.38

Further developments towards the asset backed Sukuk might lead to a further diversification into a real quasi equity based asset class in its own right, either only for the (more risky) project financings that do not generate fixed income streams but maybe also for the more stable income generators, where the pricing could be (more or less) aligned with the fixed income bond markets for the latter and with a more deviant pricing for the first.

Tapping capital markets in Islamic environments with Sukuk may further give any (conventional) issuer competitive advantages over the issuer of conventional bonds in said jurisdictions.

Further Reading:

There is abundant literature available on the subject; here are just a few:

1. Abdelkader Thomas (ed), Sukuk – Islamic Capital Markets Series (Sweet & Maxwell, 2009),p 433.

► Paul Wouters

1 It might be appropriate – but not necessary – to first have access to the first article (quote) of the contributor to the magazine.

2 That are characterised by long term capital risk exposure and fluctuating capital gains “if and when” profit. Islamic equity markets have the same characteristics, be it that there are industry screenings (permissible and non-permissible activities) and financial screenings (avoiding too much exposure to interest bearing revenue, non-permissible revenue streams and also avoiding too much liquidity. A short listing of such screenings can for instance be found at the Dow Jones Islamic Indexes (http://www.djindexes.com/islamicmarket/– as accessed Feb 28, 2011).

3 See, however, headings “Asset Backed and Asset Based” and “Conclusion”.

4 Compare http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stock_marketand http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bond_market(as accessed Feb 28, 2011).

5 Some items more or less debated in the different schools of Islamic thought.

6 AAOIFI Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (Bahrain) – AAOIFI Standard 17(20 – as quoted Securities Commission Malaysia, Islamic Capital Market – Vol 5 – The Islamic Securities (Sukuk) Market (Lexis Nexis, 2009), p 9.

7 Source : IFSB Islamic Financial Services Board (Malaysia) – IFSB Standard 7 – Capital Adequacy requirements for Sukuk, securitisations and real estate investment, para 1.1 (version January 2009).

8 Malaysia Securities Commission – Guidelines on the Offering of Islamic Securities 2004 – Para 1.05(a) – as quoted Securities Commission Malaysia, Islamic Capital Market – Vol 5 – The Islamic Securities (Sukuk) Market (Lexis Nexis, 2009), p 9.

9 In Sukuk = Islamic bond.

10 A statement of debt, similar to an IOU. Bonds are issued by governments, companies, other entities and individuals in return for cash from lenders and investors. The borrower pays interest to the lender or investor throughout the life of the bond. http://www.anz.com/edna/dictionary.asp?action=content&content=bond (as accessed Feb 28, 2011) – Bond – financial document – an official paper given by the government or a company to show that you have lent them money that they will pay back to you at an interest rate that does not change. http://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/british/bond_2 (as accessed Feb 28, 2011) – Bond – an interest-bearing certificate of public or private indebtedness. http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/bond (as accessed Feb 28, 2011).

11 An Islamic debt could for instance be the still outstanding amount on the deferred payment of a Murabahatransaction, a payment obligation as per Ijarah/ leasing agreement etc.

12 Whilst it arguably is a way to make the investor understand and grasp the financial instrument / proposal, it indeed might create fundamental misunderstandings at the same time.

13 Otherwise money would be traded and that can only happen at face value. The ratio to be maintained could differ depending on the jurisdiction. Thresholds are also put in place by the Malaysian Securities Commission for the presence of Islamic debt papers in the Malaysian Sukuk.

14 See Paul Wouters, “The use of the Contract of Sale in Islamic Finance - General Concepts”, Singapore Law Gazette, September 2010 issue. (quote) – “where in the Ijarahstructure, the asset stays on the books and is leased out for the rent for a longer period, in the Murabahahstructures the asset(s) is / are bought and instantly sold down to the client with a deferred payment and mark up (profit). The Murabaha; therefore, is a mostly cash liquid operation”.

15 In the Musharakah; the two partners contribute capital in the form of money and/or (depending on the Mazhab) expert valuated assets. The two partners manage the partnership. Profits are split according to agreement, loss is borne according to capital contribution.

16 In the Mudarabah, one partner is the capital contributor (Rabb al-Mal)and the other partner contributes his expertise / labour (Mudarib). Profits are split according to agreement, loss is borne by the Rabb al-Mal.

17 Murabahasale with deferred payment and pre-agreed profit / Salam forward sale of not yet existing goods / Istisna’– construction of individualised asset / BBA – sale against mark up and deferred payment.

18 Investment Agency.

19 Abstraction will be made of relevant Shariah issues that accompanied the structuring of the issuances. The same diversity can be found at the other types of Sukuk.

20 As described in Mahmoud A. El-Gamal, Islamic Finance – Law, Economics, and Practice(Cambridge University Press, 2006), pp 5-7.

21 As described in Securities Commission Malaysia, Islamic Capital Market – Vol 5 – The Islamic Securities (Sukuk) Market (Lexis Nexis, 2009), p 70.

22 Ibid, p 78.

23 Source : IFSB Islamic Financial Services Board – Standard 7 – Capital Adequacy requirements for Sukuk, Securitizations and Real Estate Investme