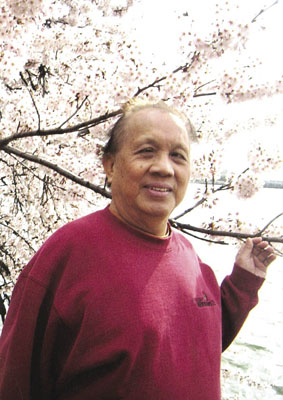

Tan Jing Quee – A Man of Letters

Tan Jing Quee was 72 when he passed away, stricken by cancer on 14 June 2011. He had been in active practice between 1970 to 1999 and was a partner of Jing Quee and Chin Joo.

He leaves behind his wife Rosemary and three children, one of whom is a practising lawyer.

He and I entered Raffles Institution in 1954. We were classmates. He completed his “A” levels (then known as HSC) in 1959 and went on to the University of Singapore where he obtained his B.A. in 1963.

The years 1955 to 1963 saw intense political activity in Singapore. The university campus was a forum for open political debate, the likes of which we do not see any more nowadays.

Jing Quee became the President of the University Socialist Club and with his passion for writing, soon became the editor of the Club’s publication, Fajar. Some of the features he wrote had strong ideological content. The momentum of political forces led Jing Quee to join the Singapore Business Houses Union as a salaried employee earning a meager pay when his cohort of graduates had cushy jobs with enviable pay packages.

Money did not drive Jing Quee. What drove him were his ideals – serving the people and fighting for independence of Malaya with Singapore as a part. Quite inevitably, he joined the Barisan Sosialis and stood as its candidate in the Kampong Glam constituency in the September 1963 General Elections against S Rajaretnam of the PAP and Harbans Singh of the SUPP. Jing Quee lost marginally by 222 votes to Rajaretnam. If not for the split votes caused by Harbans Singh who scored about 2,000 votes, Jing Quee would have defeated Rajaretnam.

Jing Quee was detained by the PAP Government in October 1963 and only released in 1966. He then decided to leave Singapore to take up law studies in England the same year.

Jing Quee breathed free air in London. An intellectual always found solace and inspiration in London. Jing Quee busied himself absorbing as much political sustenance as he could, dividing his time between law and world affairs. The anti-Vietnam rallies, anti-Apartheid protests and the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament marches filled the news columns. Jing Quee was in his element. He read voraciously and attended many talks, workshops and conferences.

Jing Quee returned to Singapore in 1970 and entered private practice. He and Lim Chin Joo set up Jing Quee and Chin Joo, a flourishing local practice. Jing Quee dealt mainly with civil litigation and earned a reputation as a diligent and meticulous lawyer. He took on powerful adversaries from larger firms and with his tenacity and sharp intellect, overcame all odds. One of his cases involved complex corporate law and his adversary was a veritable authority on corporate law. He won.

At the Bar, Jing Quee was known for his courtesy and accommodating nature. Unlike some of today’s lawyers whose primary motivation is costs, Jing Quee was obliging to his opponents. He never opposed for the sake of opposing. He did not take on cases just to earn fat fees. The case had to have some merit and had to meet his sense of fair play.

While carrying on a busy practice Jing Quee found time for his favourite pastime – reading and writing. His was “a chainless mind” if I may quote Byron.

He wrote extensively, both poetry and prose. He published several books: a collection of short stories ranging from other-worldly topics as in The Chempaka Treeand a political reminiscence, almost autobiographical, in The Cul-de-Sac. His books on poetry from Love’s Travelogueand Our Thoughts are Freerange from the very personal and gentle as the one on his first grandchild to the scorching condemnations of his jailors when he dealt with the torture he suffered in detention. Jing Quee’s landmark works are the Comet in Our Sky, the Fajar Generationand The May 13 Generationwhich he edited together with his friends.

Jing Quee was not a one-dimensional man. He was multi-talented and was a sportsman as well. He played soccer and hockey for his school and in his later years he was a keen golfer.

He loved travelling with his wife and tasting the national dishes of the countries he visited. He led a balanced life but chose to retire early to devote time for more creative pursuits. The poem he wrote on his retirement should serve as a guide to all of us. If I may quote the two closing verses:

I have come full circle

I have learnt once more

to be reminded of a simple adage:

more than your body,

your mind and your heart need nourishment.

Life’s journey

is not half spent

the seasons pass more noticeably

Still there are years to come

things to do

tasks to complete

journeys to take.

►Dr G Raman

G R Law Corporation