Introduction

|

NOTICES |

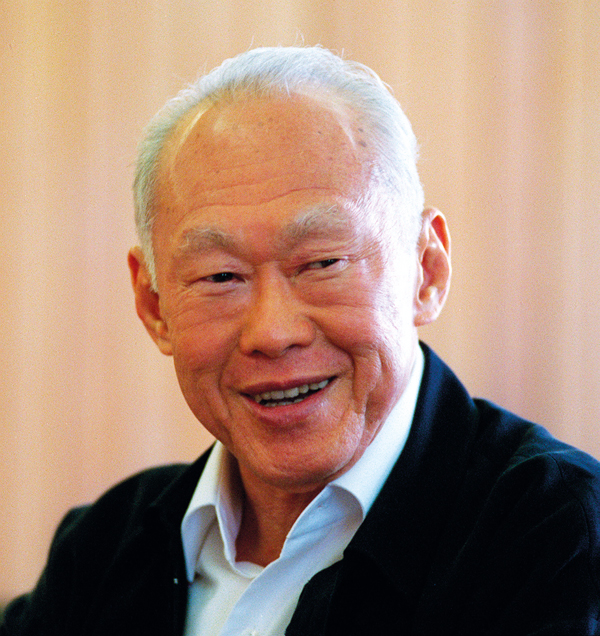

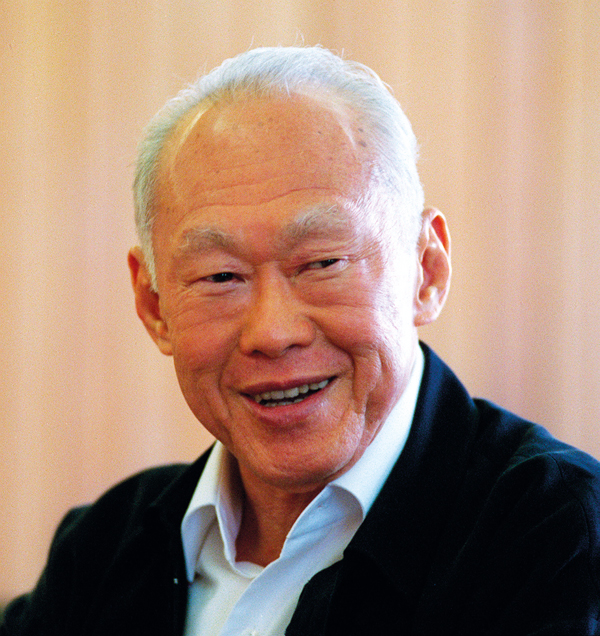

| In Memoriam |

Lee Kuan Yew’s Legacy as Lawyer

Introduction

The recent outpouring of national grief over Lee Kuan Yew’s passing has fuelled quests (both public and private) to search out the secrets in our nation’s first Prime Minister. Singaporeans want to know more about the man and the mysteries behind the man who defined Singapore and, by extension, our lives in this island state as we know it. To meet this need, the National Museum of Singapore has opened an “In Memoriam” exhibition since 25 March chronicling Lee Kuan Yew’s life and political career. For lawyers, revelations about the legendary figure has an added significance. Lee Kuan Yew was, after all, one of our own.

Surprisingly, however, precious little has been written about our founding father’s legacy as a lawyer. This narrative serves to synthesise some of the available information, supplement the literature and serve as a remembrance piece. If it has the effect of surfacing to light little-known and obscure facts about Lee Kuan Yew as lawyer to the reader, the writer would have also achieved a subsidiary objective.

Return to Singapore and Pupillage

We pick up the threads of the career narrative in 1950 when Lee Kuan Yew and Kwa Geok Choo (by then Mrs Lee Kuan Yew) returned to Singapore having been already secretly married in Stratford-upon-Avon in December 1947. Mr and Mrs Lee were both offered places for pupillage at Laycock & Ong, a thriving law firm in Malacca Street.

On 7 August 1951, having completed one year of pupillage at Laycock & Ong earning $500 a month, Lee was called to the Bar. “… dressed in somber clothes and [having] donned our barrister’s robes complete with white tabs and, in [his] case, a stiff wing collar”. In his memoirs, The Singapore Story, Lee recounted the importance of the occasion. The entire Bar had 140 members. Only some 10 new lawyers were admitted each year. Rene Eber, a respected elderly Eurasian lawyer moved the mass call with what Lee remembers to be a gracious little speech.

Post-call, Geok Choo practised conveyancing and draftsmanship. Kuan Yew did litigation.

Kuan Yew, the Pro Bono Publico Champion

Even in his fledgling years as a legal eagle, Lee’s career careered rapidly. He used his intellectual prowess and legal knowledge to optimal effect to help the masses; particularly, the unionists. The seeds were being sown for the rise and rise of a pro bono publico extraordinaire. Well-known anecdotes of Lee’s advocacy pepper the biographies and autobiographies of his life. Some of these stories are summarised next.

In one instance, Lee stood up for Malay hospital attendants who were poorly paid and resorted to rummaging through dumpsters to forage for leftover food to supplement their meagre meals. Stunningly accused of pilferage by the local hospital, these attendants faced the threat of disciplinary action. As perplexing as it would have been for the accused (and even for us today), how could such dire straits economically be considered theft? All they were doing was “just picking up what the hospital was throwing away to feed their hungry children” (recounted in Yap, Lim and Leong Men in White, The Untold Story of Singapore’s Ruling Political Party (“Men in White”).

Mofradi Bin Haji Mohamad Noor, then hospital worker and chairman of the Singapore Medical Worker’s Union turned to the Union’s legal advisor for assistance. The young and earnest lawyer wrote a letter to the management that niftily did the trick: it explained the situation and satisfactorily resolved the matter. It was not just the result that left an impact; it was also Lee Kuan Yew’s “bedside manners” that left a deep and abiding impression on the Malay hospital workers. It was quintessential Lee Kuan Yew as we know him: practical and direct. Yet also, friendly and modest. Mofradi recalled: “For example, when he attended meetings, he would not sit in front; he would sit among us”.

According to Men in White, Mofradi’s account “had an unerring ring of familiarity which kept recurring in interviews with many former trade union leaders of the period – a union would have an industrial dispute, a work stoppage or a go-slow, or it would go on strike or enter into arbitration, and hey presto, its legal adviser would turn out to be Lee Kuan Yew”.

Singapore Barber Shops and Hair-Dressing Salons Workers’ Union President, Lin You Eng was once wrongly charged for vandalism. He was defended and ultimately cleared of all charges by the Union’s legal advisor. Lin remembered Lee as being very helpful and patient when dealing with them during the incident. “He spoke to us in halting Mandarin. He had no airs and showed he was willing to listen to the union members”.

Former journalist, minister and diplomat, Othman Wok, Secretary of Singapore Printing Employees Union (“SPEU”), had gone on strike against British-owned Straits Times and the dismissal of a union official. No prizes for guessing who their legal advisor was. Lee gave them sound advice – warning the union that it would lose the battle as it was facing a “very powerful employer” who represented British interests. He advised the strikers to go back to work and offered to resolve the dispute for them. The Union wisely heeded Lee’s advice.

Lee’s memorabilia shows all-and-sundry correspondence from trade unions naming Lee, or inviting him to be, their legal advisor. There were no fewer than 50 unions and associates – from the humble to the everyday to the esoteric. His list of clientele included the following:

1. East Coast Mining and Industrial Workers’ Union.

2. Amalgamated Malayan Pineapple Workers’ Union.

3. Malayan Gold and Silver Workers’ Union (Singapore branch).

4. Singapore Spring Workers’ Union.

5. Singapore Itinerant Hawkers and Stalls Association.

6. Singapore Chinese Liquor Retailers’ Association.

7. Singapore City Council Night Soil Worker’s Union.

8. Singapore Printing Employees’ Union.

9. Singapore Union of Journalists.

Lee’s list would hardly be the envy of a modern-day lawyer showcasing his client list.

According to Lee’s memoirs, many unions sought him to be legal advisor when he gained public prominence. “We decided we would not turn them down so I became honorary advisor this, legal advisor that …. I used to go to some of their annual dinners or meetings to touch base with them”.

The Straits Times, 23 March 2015 edition in an article captioned “Union Rabble Rouser” succinctly comments: “Soon Mr Lee built a reputation as a champion of social underdogs. He became legal adviser to more than 100 unions and associations within two years”.

But the case that propelled Lee into an unprecedented prominence in the public’s eyes was a pay dispute between the Singapore Post and Telegraph Uniformed Staff Union and the colonial authorities in 1952. It arrived at the time of another, more personal, arrival. Union leaders had asked Lee to be their legal advisor several days before the birth of his first child, Lee Hsien Loong. Geok Choo’s memory of this in Men in White captures the hidden euphoria of that moment: “People would think he’d be cooing over the baby all the time instead of talking about union matters. But I think he was quite pleased at the prospect of acting for this union.”

Throughout the 13-day strike by the P and T Union (as it was better known), all mail services ground to a halt. This predictably, unnerved British officials. Lee wore the hat of legal advisor, official negotiator and eloquent spokesman with aplomb.

In Lee Kuan Yew’s reminiscence during his eulogy at his late wife’s, Geok Choo’s, passing at the funeral service at Mandai Crematorium, 6 October 2010 he said: “That February [in 1952], I was asked by John Laycock, the Senior Partner, to take up the case of the Postal and Telecommunications Uniformed Staff Union, the postmen’s union. They were negotiating with the government for better terms and conditions of service. Negotiations were deadlocked and they decided to go on strike. It was a battle for public support. I was able to put across the reasonableness of their case through the press and radio. After a fortnight, they won concessions from the government. Choo, who was at home on maternity leave, penciled through my draft statements, making them simple and clear.”

The dispute hinged on $10. The difference between the Government’s offer of $90 and the postmen’s demand of $100 on the maximum pay. The demand for the reasonable and small differential was met by an inexplicable intransigence from the authorities. Despite the massive service disruptions, public sympathy and support were strongly with the postmen. Even the press and pro-British legislative councillors sympathised with the unionists. Eventually, the pressure took its toll and the Government of the day caved in. The case became a cause celebre and Lee Kuan Yew, a household name.

No Charge for Legal Fees

In his memoirs The Singapore Story, Lee said that he accepted the postmen’s case without charging for legal fees.

In a speech entitled The lawyer and his vision for Singapore on 4 June 2010, Simon Chesterman succinctly observed: “[Lee’s] early clients were often trade unions and associations, meaning that he earned considerably less than he could have as a lawyer. When the cause was worthy and the clients needy, he waived his fees entirely …”

The Straits Times (23 March 2015) under a news headline captioned “Union Rabble Rouser“ reported in similar vein:

"As a newly minted lawyer who had just returned home from Britain, the young Mr. Lee Kuan Yew devoted time to helping the unions and other vulnerable groups in their run-ins with the British … These cases rarely raked in the big money, much to the chagrin of his firm, Laycock & Ong."

Lee’s employers were certainly not amused. In a letter to Lee, his boss John Laycock complained that the firm had “suffered” from all his union cases and that it “must not take on any more of these wage disputes.”

The editors of Men in White offer the following commentary: “Obviously, the lawyer was not in it for the money. The unions comprised lowly paid workers who could barely afford to pay his legal expenses.”

If Lee had really courted material rewards, he would have joined some of his peers in servicing well-heeled clients including those hailing from a few big British trading houses, banks or doing lucrative conveyancing work. He chose the path less-travelled.

Regional Fame and Inception of Lee & Lee

Lee’s fame was not just limited to Singapore. When Utusan Melayu stalwart, Abdul Samad Ismail, was detained in 1951 for anti-British activities, his newspaper hired Lee as his lawyer. Living in retirement in Petaling Jaya in 2002, the doyen of journalism whose controversial career straddled both sides of the Causeway was reportedly both vivid and livid at the recollection. Another leading lawyer demanded $15,000 from him to do his case. Lee famously charged a token sum of $10. He subsequently defended university students who had worked on the University of Malaya undergraduate newspaper, Fajar.

In 1955, perhaps sensing the need for greater autonomy as to the choice and shape of his practice, Lee together with his brother and wife, set up one of Singapore’s best known local law firms: Lee & Lee.

Court Appearances

A quick survey of some cases he was involved in show him advancing arguments as Counsel in distinctly different and specialised areas of practice: criminal, family, landlord and tenant law and (predictably) judicial review applications. Lee Kuan Yew was:

• Amicus curiae in R v Tan Ah Inn & Ors [1953] 1 MLJ 65.1 on the meaning of the word “frequent” in s 10(2)(b) of the Dangerous Drugs Ordinance, 1951.

• Counsel for the successful appellant in Lim Yam Heng v Choo Swee Choo (f) [1955] 1 MLJ 176.1. In that case, the appellant was ordered to pay the sum of $50 monthly for the maintenance of his wife, the respondent, under s 2(1) of the Married Women and Children (Maintenance) Ordinance, 1949. At first instance, the learned Magistrate made the order as he found that the appellant had made no effort to take his wife home even though the appellant informed the Court that he wanted his wife to return to the matrimonial house. On appeal, Tan Ah Tah J held that there was no legal obligation on the husband’s part to take positive steps to bring the wife home to fulfil the conditional maintenance order – the condition being that she lives with him in the matrimonial home. The order made by the learned Magistrate was held therefore to be wrong and set aside. What is significant to note is the pro-active conciliation stance of Lee Kuan Yew reported at the tail end of the judgment. The report states “the appeal having been allowed, counsel for the appellant intimated, after discussion, that he would seek the aid of the Social Welfare Department in an endeavour to bring the parties together”.

• Counsel for the Respondent/Plaintiff in Lum See On v Chan Kit Yong (f) [1956] 1 MLJ 40 that held, inter alia, that the relevant date for determining the rights of a landlord and tenant of rent-controlled premises is the date of the hearing. As the Defendant/Appellant ceased to be the legal personal representative of the original tenant when the action was heard, she was not entitled to rely upon the provisions of the Control of Rent Ordinance as at that date to defeat the plaintiff’s claim for possession at common law.

• Counsel for the successful appellant in Cherian Varughese v Aminah Radin Osman [1958] 1 MLJ 221. In a robust position adopted at first instance before the District Judge, he submitted a plea of no case to answer that was rejected. On appeal, the critical legal issue was the meaning of “demand” in s 15(1)(a) of the Control of Rent Ordinance. It was held that the words of that statute which requires a “notice of demand in writing” meant that “demand” should be construed in its popular sense as opposed to meaning a formal demand made in accordance with the strict rules of common law. In that case, as the trial Judge based his finding on the question of reasonableness purely on the fact of irregularity as payment of rent and failed to direct his mind to the facts that led to such irregularity, a new trial was ordered.

• Counsel for the applicant (Ahmad Ibrahim was Senior Crown Counsel) in an application for an Order of Prohibition to restrain a Commissioner appointed under the Inquiry Commission Ordinance from acting on the ground that he was biased: In re Application by Ong Eng Guan for an order of prohibition in Re Appointment of S H D Elias [1959] 1 MLJ 92. The Attorney-General raised a preliminary objection that the Writ of Prohibition did not lie against a Commissioner appointed under the Inquiry Commissions Ordinance, as the Commissioner had no power to determine questions affecting the rights of subjects and was, therefore, not a judicial tribunal. Rose CJ upheld the preliminary objection. However, the Court considered it to be a “borderline case” and that “The decided cases, however, indicate that courts, naturally enough, are slow to grant orders of prohibition on the head of bias except on the clearest grounds and, while it may be that I regard these highly charged political matters with too detached an eye, I have come to the conclusion that the Commissioner in question, who, I have no doubt, accepted his exacting assignment out of a sense of public duty and who is a person of standing in his profession and the community at large, would not in fact be biassed (sic) by the considerations to which I have referred”.

• Counsel for the appellant in the District Court Appeal No. 28 of 1952 hearing in Toh Whye Teck v The Happy World Ltd [1953] 1 MLJ 171. Whitton J commended Lee Kuan Yew, for having “argued with great ability”.

• Counsel for the successful appellant in Tan Kia Gan v Tan Siok Hoon (F) [1959] 1 MLJ 38. This was a family case in which Rigby J of the Penang Court also gave a judicial commendation in closing that “in conclusion I would express my indebtedness to both Counsel for their arguments ...” The other Counsel was Eusoffe Abdoolcader, amicus curiae, in that case later to be appointed as Malaysian Supreme Court Judge.

No Motivation of Financial Gain

Former Straits Times news editor Felix Abisheganaden who was acquainted with Lee in the decades of 1950s and 1960s has quipped: “You can never say that he was ever in his life after any kind of financial gain – never, never, never”.

The editors of Men In White suggest that Lee’s motivations were to get involved in politics. What better way to cut your political milk teeth than to take up the cudgels on behalf of underpaid workers = an important political base?

But in the final analysis, does it matter from the perspective of providing pro bono legal services, what Lee’s motivations were? For who knows what lurks in the human heart in even the most ostensible altruist. Perhaps, the right question to ask is whether the indigent in Lee’s day were helped. Whether men and women in the street who would not have otherwise had their day in Court, or faced legal challenges affecting their lives, had legal aid and legal advice from a learned friend. A learned friend in need.

Conclusion

In summary, Lee was passionate about justice. He took up the cause for the poor and needy of his day (epitomised by his representation of the trade union rank and file). He enabled the indigent, whom few fellow members of the Bar cared about, to gain access to justice. This was unparalleled for that era of post-World War II lawyers. As a local member of an elite group of lawyers called to the Bar, he could have chosen to look inwardly to build personal wealth. Instead, he looked outwardly to do pro bono publico.

By exemplifying excellence in the conduct of his cases, as the snapshot from the reported cases of his Court appearances above shows, Lee also left an indelible mark as a thought leader in legal practice. Who knows, in an alternative reality, how Lee’s courtroom advocacy could have helped develop Singapore jurisprudence in niche areas of litigation expertise?

But while his sojourn in the practice of law was all too short, Lee’s ethos as a lawyer will not be forgotten. Charles Dickens wrote “There are strings in the human heart that had better not be vibrated”. Conversely, however, there are strings in the human heart that when vibrated, resonate in other human hearts. Lee’s heart strings vibrated, over the corridors of time, and resonate in the hearts of men and women who seek to practice law excellently yet with a social conscience. And that, I submit, is the lasting legacy he has left us as lawyers. A legacy both endearing and enduring for generations to come.

► Gregory Vijayendran*

Rajah & Tann Singapore LLP

Vice-President

The Law Society of Singapore

* The author is grateful to Ronald Wong, Jonathan Cheong and Jason Gabriel Chiang for their research that contributed to this article. All errors and omissions are mine.

Bibliography

1 Yap, Lim and Leong, “Men in White, The Untold Story of Singapore’s Ruling Political Party”.

2 The Singapore Story, Memoirs of Lee Kuan Yew (Singapore Press Holdings, 1998 Reprint).

3 Simon Chesterman, “The lawyer and his vision for Singapore”, from a speech delivered on 4 June 2010 at the ceremony for conferment of a honorary degree of doctor of laws on Lee Kuan Yew (Straits Times, 5 June 2013 edition at A20).

4 “Union Rabble Rouser”. Straits Times (23 March 2015 edition).

5 Corfield, “Historical Dictionary of Singapore” (2011 Edition).

6 Eulogy by Minister Mentor Lee Kuan Yew at the Funeral Service of Mrs Lee Kuan Yew, Mandai Crematorium, 6 October 2010