Lee Kuan Yew’s Legal Legacy

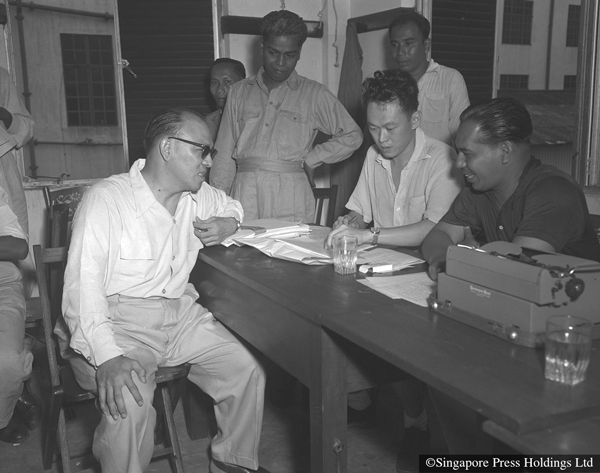

Mr Lee Kuan Yew providing legal advice to a group of workers, circa 1952. Source: The Straits Times © Singapore Press Holdings Limited. Permission required for reproduction

Introduction

Lee Kuan Yew joined Laycock & Ong in 1950 as a pupil. After getting called to the Bar in 1951, he became a general litigator practising in the areas of contract, criminal and land law. Also as a new young lawyer with Laycock & Ong, Lee attended to UCB’s (United Chinese Bank) simpler work.1 Making a name for himself as a skilled advocate and negotiator, Lee remained at Laycock & Ong for five years before setting up his own firm, Lee & Lee, with his wife and brother Dennis in 1955. His practice covered not only Singapore but also the Federation of Malaya and British Borneo.

When Lee Kuan Yew and his wife were called to the Bar in Singapore in 1951, the entire Bar had 140 members with only 10 new members being admitted each year. Asians were a minority within the bar and part of a professional and judicial hierarchy almost exclusively British.2 There was a gradual localisation of the legal profession and by 1960 no Caucasian lawyers were added to the rolls.3

Lee also had his first experience in politics when he served as an election agent in the 1951 Legislative Council elections for his boss, John Laycock, who ran under the banner of the pro-British Singapore Progressive Party (“SPP”). After losing his Katong seat in the 1955 elections, Mr Laycock decided to leave politics.

Post-war Singapore witnessed nascent nationalism and the formation of local political parties. Given their ease in public speaking and powers of reasoning, lawyers were active in political campaigning and the formation of political parties. Other famous lawyer politicians included John Laycock, CC Tan, NA Mallal and David Marshall.4

It was as legal adviser to unions that Lee Kuan Yew cut his political teeth. He was legal adviser to more than 100 unions and associations by the time the People’s Action Party was formed in 1954, ahead of a legislative assembly election the following year, the first election that saw elected members outnumbering those appointed by the British. This did not go unnoticed by the bosses of Laycock & Ong. A 1953 letter from the law firm’s boss, John Laycock, was addressed to Lee Kuan Yew, saying that he should let the firm “have full information” before he accepted more “lengthy” cases of wage disputes.

Rent Control Cases

The cases that Lee Kuan Yew took on reflected the social and historical milieu, for instance, there were a few cases on the Control of Rent Ordinance. The 1953 Control of Rent Ordinance was passed against a background of accommodation shortage caused by damage to property during the Second World War, the return of people who left Singapore during the Japanese Occupation and the rising birth rate. As a result, rent restriction was introduced to address the pressure on rents.

In Chew Khai and Ors v Poh Tai Company (Sued As A Firm) [1957] MLJ 43, Lee Kuan Yew obtained an order for possession for the landlord. The Court did not agree with his argument that the demolition of the building was necessary in the interests of public health. However, his fallback argument succeeded and the Court found that there was clear and compelling evidence that its demolition was necessary in the interests of town improvement.

In Toh Whye Teck v The Happy World Ltd [1953] MLJ 171, Lee Kuan Yew appeared for the appellant in an appeal from the District Judge’s decision in favour of the respondent for recovery of possession under s 14(1)(j) of the Control of Rent Ordinance. On appeal, the issue was “on whom does the burden lie to show what sums came within the section and what payments are saved by this provisions relating to Municipal services”. Even though the appeal was dismissed, Lee’s advocacy drew praise from the Court:

Mr Lee Kuan Yew has argued with great ability that some evidence at least should have been produced by the plaintiff as to the payments made for Municipal services. If that evidence was forthcoming he would concede that the burden is then shifted to the defence. This argument is not to be dismissed lightly, but on reflection I consider it is sufficient for the plaintiff, if, as in this case, he establishes prima facie that the rents received by the tenant exceeded in the aggregate 75% of the rent paid to himself.

Lee Kuan Yew appeared for the Respondent/Plaintiff in Lum See On v Chan Kit Yong (f) [1956] 1 MLJ 40, a complex matter that involved an interplay between probate law and the Control of Rent Ordinance. The Court held that the relevant date for determining the rights of a landlord and tenant of rent-controlled premises is the date of the hearing. As the Defendant/Appellant ceased to be the legal personal representative of the original tenant when the action was heard, she was not entitled to rely upon the provisions of the Control of Rent Ordinance as at that date to defeat the plaintiff’s claim for possession at common law. The Court noted that during the course of the hearing of the appeal, “counsel on both sides ranged over a wide field, raised numerous points of law and modified their submissions with unusual dexterity and celerity”.

He also appeared as counsel for the successful appellant in Cherian Varughese v Aminah Radin Osman [1958] 1 MLJ 221. At first instance before the District Judge, Lee Kuan Yew submitted a plea of no case to answer that was rejected. On appeal, the key legal issue was the meaning of “demand” in s 15(1)(a) of the Control of Rent Ordinance. It was held that the words of that statute which requires a “notice of demand in writing” meant that “demand” should be construed in its popular sense as opposed to, meaning a formal demand made in accordance with the strict rules of common law. In that case, as the trial Judge based his finding on the question of reasonableness purely on the fact of irregularity as payment of rent and failed to direct his mind to the facts that led to such irregularity, a new trial was ordered.

Criminal Matters

One of his first cases after getting called to the Bar was a criminal matter. He defended four men among 13 charged with having committed murder by causing the death of Charles Joseph Ryan, a non-commissioned officer in the Royal Air Force. This was committed during the Maria Hertogh riots in December 1950, where white men and women were killed indiscriminately. The trial lasted nearly two weeks and was conducted before a Judge and a jury of seven. Three of Lee’s clients were acquitted and the fourth was sentenced to five years imprisonment.5 It was this case that shaped Lee’s views on the jury system.

As there was widespread abuse of opium among residents in Singapore, legislation to make opium smoking illegal was introduced in 1946. In addition, the Dangerous Drug Ordinance was enacted in 1951 to specify opium, cannabis, morphine, cocaine, and heroin as dangerous drugs and unauthorised possession as an offence often requiring mandatory treatment and rehabilitation for drug addicts. This was the predecessor of the Misuse of Drugs Act.

Lee Kuan Yew appeared as amicus curiae in the case of R v Tan Ah Inn & Ors [1953] MLJ 65, where the key issue was the meaning of the word “frequent” in s 10(2)(b) of the Dangerous Drugs Ordinance. Lee highlighted to the Court a number of English cases where the word “frequent” had been extended to mean being in a place long enough for the purpose or intent in hand. The Court held that in respect of s 10(2)(b), it was not necessary to prove intent or purpose. It distinguished the English cases cited because in those cases, the wrongful purpose or intent was an essential ingredient of the charge. As such, the Court was of the view that the word “frequent” could only be given its ordinary meaning of “visiting often”, so that a person committed an offence under this section if he visited one set of premises often, or if he visited a number of similar premises on one occasion each. It was conceded by the crown counsel that one casual visit would not be “frequenting”.

In Goh Leng Sai v R [1959] 1 MLJ 121, Lee appeared for the appellant who was convicted in the District Court of the following Charge:

That he, on or about 16 February 1957, at about 8.00 pm at Singapore, having a contract with the Singapore City Council, did corruptly give to an agent, namely, GM Richards, the acting Chief Engineer (Construction) of the Sewerage Department of the City Council, the sum of one thousand dollars as an inducement or reward for showing favour to himself in relation to his principal`s affairs, and thereby committed an offence under s 3(b) and punishable under s 4 of the Prevention of Corruption Ordinance (Ch 121).

Lee Kuan Yew argued on behalf of the appellant that there was insufficient evidence that the appellant had a contract with the City Council, the only evidence adduced by the prosecution being oral evidence. The Court dismissed the appeal, holding that the existence of a contract or contractual relationship may be proved by oral evidence. It held that proof of the existence of a contract must be distinguished from proof of the terms of a contract. In this regard, s 92 of the Evidence Ordinance does not apply to proof of the existence of a contract. Section 64 of the Evidence Ordinance requires the production of a document only if it is desired to prove the contents of the document.

It is noteworthy that the Court in a later decision, Ng Kong Yue & Anor v Regina [1962] MLJ 67, cast doubt on Goh Leng Sai. The Court was of the view that having regard to ss 4 and 5 of the Prevention of Corruption Ordinance, it was important that the contract was proved by admissible evidence. The contract not being collateral but of the essence of the prosecution case, it could not be proved by parol evidence.

Other Significant Cases

In K Abdul Gaffoor v Regina [1954] MLJ 154, Lee Kuan Yew acted for the complainant in a trade mark counterfeiting matter. The material issue was the date at which the offending labels were made. The Court held that a label which is not counterfeit when made cannot become counterfeit through the subsequent registration of a trade mark by someone else.

Singapore’s bankruptcy regime started with the Bankruptcy Ordinance of 1888 which was introduced in 1888 when Singapore was part of the British Straits Settlement. The Ordinance was based on the English Bankruptcy Act 1883. For 107 years, the structure and laws established by the Ordinance remained intact. In Koh Hor Khoon v R [1955] MLJ 196, Lee Kuan Yew appeared as assisting counsel for the appellant. The appellant in this case was convicted by a District Judge on two charges under s 107(1) of the Bankruptcy Ordinance (Cap 45) of pledging quantities of Japanese galvanised iron sheets he had obtained on credit and had not paid for. At the trial, a certified copy of the notes of evidence taken at the public examination of the appellant in bankruptcy proceedings was admitted as evidence. One of the principal points argued on appeal was that the certified copy of the notes of evidence was wrongly admitted in evidence.

The Court did not allow the appeal, having decided that the notes of the public examination in this case were rightly admitted in evidence. Its decision was premised on the wide power given to the Court to put questions to the bankrupt and the unqualified obligation of the bankrupt to answer them. Had the legislature intended to preserve to a bankrupt in those proceedings the well established ordinary right of a witness not to incriminate himself, this would have expressly provided for. In this regard, the Court held that the specific provisions for procedure to govern the public examination of a bankrupt must overrule the general provisions of law contained in the Evidence Ordinance.

Conclusion

This article has examined some of the cases that Lee Kuan Yew had appeared in. During his nine years in practice, Lee Kuan Yew’s name appeared frequently in the law reports, recording his appearances in cases which contributed to the development of the law here and in Malaya.6

► Debby Lim

Member, Publications Committee

The Law Society of Singapore

Notes

1 Speech by Senior Minister Mr Lee Kuan Yew at the Opening of the United Overseas Bank (“UOB”) Plaza on Sunday 6 August 1995.

2 Dezalay and Garth, Asian Legal Revivals: Lawyers in the Shadow of Empire, p98.

3 Available at:

4 Ibid.

5 The Singapore Story: Memoirs of Lee Kuan Yew

6 Citation by the Attorney General, Mr Tan Boon Teik (1990) 2 SAcLJ 152

This barrister's wig was one of two bought by the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew and his wife, Madam Kwa Geok Choo, when they were admitted to the Bar. Source: The Straits Times © Singapore Press Holdings Limited. Permission required for reproduction